FREE-REED JOURNAL

Vol. I, 1999, pp. 19-37 |

| |

Classical Music for Accordion

by African-American Composers |

| |

The Accordion Works of

William Grant Still (1895-1978)

And

Ronald Roxbury (1946-86) |

| |

ROBERT YOUNG McMAHAN |

| |

| |

|

On Saturday, April 24, 1960, the New York Times announced that “William Grant Still's 'Aria for Unaccompanied Accordion,' the eighth work commissioned by the American Accordionists' Association, will have its first performance at Town Hall May 15."1The previous seven commissions were by no-less-significant names in American music, beginning with Paul Creston (Prelude and Dance ), in 1957, and continuing with Wallingford Riegger, Virgil Thomson, Carlos Surinach, Robert Russell Bennett, and Henry Cowell through 1959. Still's Aria was contracted in 1959 also, on December 1st.

The American Accordionists' Association was founded in 1938 by twelve of the truly first accordion virtuosi in history, including such seminal pioneers as Pietro Deiro, Pietro Frosini, Charles Magnante, Joseph Biviano, Charles Nunzio and Anthony Galla-Rini. Among the stated goals of the A. A. A. was the intention "to publish literature to be of service to accordionists."2 Regarding this point, however, nothing was specifically said about building an original literature for the instrument. A future board member of the organization, Elsie Bennett, who was a music student at Columbia University in the mid-1940s and allowed to use the accordion as her major instrument, would eventually address that all important issue.

|

| |

|

1"Hemidemisemiquavers," New York Times, April 24, 1960, p. 11, col. 6.

2The Credo of the A. A. A. may be read in full in the 1963 Annual of the American Accordionists' Association, 1963, 5. Additional articles of interest in the same publication are Theresa Costello (A. A. A. Secretary), "Our Silver Anniversary, 1938-1963" (p. 1), and Eugene Ettore (A. A. A. President), "An Open Letter from Eugene Ettore, President American Accordionists' Association" (p.3). See also <www.accordions .com/aaa> .

|

|

| |

One of her teachers at Columbia was the composer and future electronic-music pioneer Otto Luening. In 1953, he convinced the A. A. A. governing board that composers needed to be commissioned and paid to write for the accordion if it were ever to gain a prestigious original repertoire. This resulted in the establishment of the Composers' Commisioning Committee, · with Bennett as the chair, a position she continues to hold energetically today, forty-six years later.3 Since Still's Aria, forty-three more commissions have been made. Names of particular distinction, in addition to those already listed, include Henry Brant, David Diamond, Lukas Foss, Ernst Krenek, George Kleinsinger, Paul Pisk, Elie Siegmeister, Jose Serebrier, Alexander Tcherepnin, Gary Friedman, and Robert Baksa.

Bennett first wrote to Still for the commission probably early in 1959, and sent him some information on the accordion and a copy of Creston's Prelude and Dance. The first surviving letter of the Bennett/Still association is from the composer to the commissioner, dated March 12, 1959, thanking her for the materials and stating that he was very impressed with the accordion's apparent capabilities.

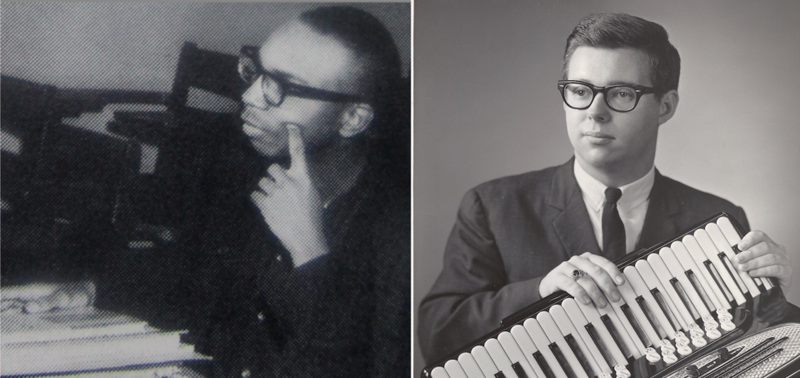

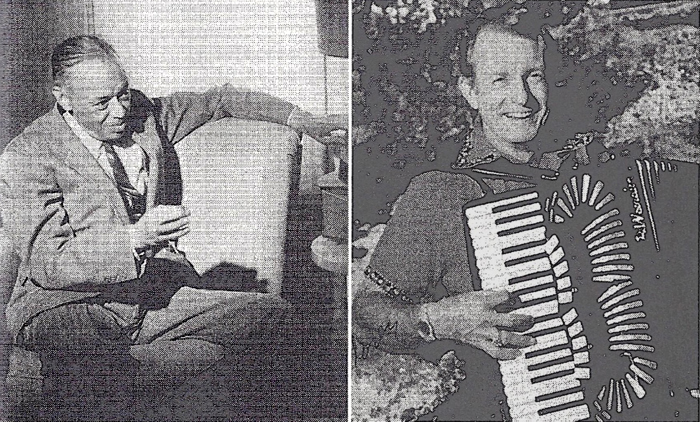

In a feature article by Elsie Bennett on Still's commission that appeared in the February 1961 issue of Accordion and Guitar World, she indicated that, since the composer lived on the other side of the continent, in Los Angeles, she asked a resident of that area, the well-known accordionist Myron Floren, of the immensely popular Lawrence Welk Orchestra and television show, to explain the instrument to Still and help edit the forthcoming work. 4Unfortunately, Floren does not mention his visit with Still in his 1981 autobiography, Accordion Man. 5But correspondence between the accordionist and Bennett (in the Bennett files) reveals the following: Bennett was advised by A.A. A. virtuoso Carmen Carrozza (to be discussed below) to request Floren's assistance. She, in tum, wrote to Floren on December 11, 1959, with this proposal, and further asked that, if he agreed to perform this task, he should also arrange to have a publicity photograph made of himself and Still. Floren responded in a January 11, 1960, letter that Still had contacted him, that they had a photograph taken, and that they had just met to work on the already in-progress Aria. Of this meeting, Floren reported the following: "His [Still's] wife [Verna Arvey] played the Aria on the piano first and then we began working from the beginning and I would play each phrase with different switches until he heard the sound that he had had in mind in writing the piece." |

| |

|

3Luening's talk is extensively described and quoted in "Otto Luening Addresses A. A. A. at Open Meeting," American Accordionists' Association News 412 (April 1953): 3, 6.

4Elsie Bennett, "William Grant Still Writes for Unaccompanied Accordion: Aria for Accordion," Accordion and Guitar World 25/11 (February 1961): 21.

5Myron Floren and Randee Floren, Accordion Man (Brattleboro, VT: Stephen Greene Press, 1981).

|

|

| |

| |

| Figure I. William Grant Still and Myron Floren, ca. 1960. Used by permission of Judith Anne Still and Myron Floren. |

| |

Still was clearly impressed with both the instrument and the artist, as a Christmas Eve, 1959, letter to Bennett that was quoted in the article attests: |

| |

My association with Mr. Floren made me realize what the instrument can accomplish in the way of virtuosity and in sustained and flowing melodies. One can no longer speak simply of "the sound" of an accordion, because of the variety of its tonal effects. After hearing some of the striking and appealing things that can be done on it, I would say that it not only has many resources, but it could very well be used with marked effectiveness in the orchestra. I am interested enough to want to again write for the accordion, and I am sure that as other composers listen to and study the instrument carefully, they, too, will share my enthusiasm for it. |

|

Still also revealed that he had worked with Sidney B. Dawson, one of the founding members of the A. A. A., a few years earlier in arranging a spiritual for accordion and chorus (title unknown), but it was not until later, when he heard a recording of Magnante playing his (Magnante's) own transcription of Bach's organ Toccata in D Minor, an item Bennett gave to all potential commissionees, that he "really began to understand what the instrument [could] do in the hands of a true artist." 6Floren confirmed this view in a letter to Bennett: |

| |

|

6Johann Sebastian Bach, Toccata in D Minor (for organ), arranged for accordion by Charles Magnante (New York: Pagani, 1941). |

|

| |

"He had listened to the records you [Bennett] had sent him and was especially impressed with some of the concert work of Magnante.”7

Still's daughter and present-day strong promoter of her father's music, Judith Anne Still, has little memory of Floren's visit, as she explains in a recent letter to me: "I have no memories of Myron Floren, except that I came downstairs one afternoon and found him (or some gentleman) in the living room, demonstrating the accordion. He was instructing my father in the instrument." (It should be mentioned here that Ms. Still would have been about sixteen years old at the time. Floren remembers her appearance that day, however, and that it was one of "many meetings" he had with Still, as he recently reported in a letter to me.) She continues, explaining that her father was "very private in his composing" and "never discussed a piece unless my mother was writing words for it. Moreover, he stopped writing in his diary in 1959, so there may be no record [of Floren's visit or of his impressions of the accordion] there;" Ms. Still also offers further explanation for the lack of further comment by her father on this matter: "In the [19]60s he was tired, discouraged and less optimistic, so that his music had a wistful, lyrical quality, and he was less likely to indulge himself in learning new instruments such as the organ and accordion . . . Just think what he could have done if he had discovered the accordion in 1921, when he began the composition of Levee Land?"8

Floren was very pleased with the piece, reporting to Bennett that he "found the Aria to be a beautiful number with many interesting color changes." He apparently thought the same about it more than three decades later, as can be observed in the letter from him to me in 1995: "I think the Aria fitted the accordion very well and was a beautiful piece of music. Very lyrical." Furthermore, his opinion of Still as a human being echoes that of practically everybody who knew and consequently loved him: "I thought he was a very fine gentleman, very quiet and unassuming. "9

Fulfilling the New York Times announcement, the world premiere of Aria did indeed take place on Sunday afternoon, May 15, 1960, at 2:30, as part of the Sano Accordion Symphony concert at Town Hall. Participating artists were Eugene Ettore, veteran accordionist and the conductor of the accordion orchestra, guest artist Myron Floren, who, as planned, premiered Aria as well as Robert Russell Bennett's Four Nocturnes (at Elsie Bennett's request), and Judy Procida, who served as narrator for a musical novelty tribute by Ettore (with words by his student Rosemarie Gerber [ now Cavanaugh ]) to Floren entitled Hey! Myron. |

| |

|

7Letter from Myron Floren to Elsie Bennett, January 11, 1960 (Bennett files).

8Personal communication from Judith Anne Still, April 14, 1995. Though trained as a writer rather than musician, Ms. Still is president of William Grant Still Music, Flagstaff, Arizona. She travels extensively, promoting her late father's music through lectures, panels, and concerts.

9Letter from Myron Floren to Robert McMahan, May 9, 1995; see also note 7. |

|

| |

The rest of the program consisted of transcriptions for accordion orchestra of such works as Mussorgsky's A Night on Bald Mountain, Donizetti's overture to Don Pasquale, and the finale of Tchaikovsky's Fourth Symphony. Floren requested from Bennett and was given about one hour of stage time. 10 In addition to the Still and Bennett pieces, he performed Fughetta, by accordionist John Gart, various transcriptions (Vittorio Monti's Czardas, Claude Debussy's Clair de lune, Aram Khachaturian's Sabre Dance, Sir Arthur Sullivan's The Lost Chord, and Ferde Grofe's "On the Trail," from , the Grand Canyon Suite), and "selected old time dances" (Clarence "Pinetop" Smith's "Original" Boogie Woogie, Les Brown's Sentimental Journey, Thomas Haynes Bayly's Long, Long Ago, and Tolchard Evans's inescapable Lady of Spain). 11 Despite this motley assortment of selections, Francis D. Perkins, of the New York Herald Tribune, gave a favorable review, saying that the two original works (the Still and Bennett pieces) possessed "melodic appeal and variety of mood," and that they "revealed their composers' understanding of the accordion's requirements and resources." 12

Over the next few years, Aria was to enjoy further momentous, mainstream exposure. Carmen Carrozza, a brilliant "third generation" virtuoso and a student of Deiro, included it in his many recitals and appearances in general contemporary music concerts, particularly in New York. Apparently more at ease with contemporary music than his older colleagues, he was responsible for playing the premieres of most of the A. A. A. commissions, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. He is still an active classical artist and one of the world's most venerated senior accordion maestri.

On February 11, 1961, Carrozza gave a recital of all-commissioned works, including Aria and two pieces by Henry Cowell and Alan Hovhaness similarly commissioned by the Accordion Teachers Guild, at the Arts Club of Chicago. The capacity audience received the new music, played on this "new instrument," very enthusiastically, according to Carrozza (there is no review, unfortunately). 13 |

| |

|

10Letter from Myron Floren to Elsie Bennett, March 30, 1960 (Bennett files).

11These selections are listed in a letter from Floren to Bennett, April 27, 1960 (Bennett files).

12Francis D. Perkins, "Sano Accordion Symphony Plays At Town Hall." New York Herald Tribune, May 16, 1960, p. 12, col. 4.

13[Elsie Bennett], "First Concert of All-Commissioned Works Presented by Carmen Carrozza at Arts Club of Chicago," A. A. A. typescript of press release, May 1961 (in Bennett files). I am indebted to Diane Haskell, librarian at the Newberry Library, in Chicago, for the precise date of the concert, a copy of the program, and acknowledgement of there being no reviews. The Accordion Teachers' Guild commissioned works on the recital were Hovhannes's Suite and Cowell's Perpetual Motion. The remaining A. A. A. compositions were Cowell’s Iridescent Rondo, Bennett's Four Nocturnes,Riegger's Cooper Square, Thomson's Lamentations, and Surinach's Pavanne and Rondo. The Accordion Teachers' Guild, a friendly rival organization of the A. A. A., was founded in Chicago in 1940. Among its past presidents are two founders of the A. A. A., Anthony Galla-Rini (for 1951-52) and Charles Nunzio (for 1962-63). See the A. T. G. webpage: http://accordions.com/atg. |

|

| |

About two months later, on April 17, 1961, he participated in the final concert of the season for the National Association of American Composers and Conductors, at Carnegie Recital Hall, playing the A. A. A. commissions, Lamentations by Virgil Thomson (the fourth commission, 1959) and Prelude and Dance by Paul Creston, as well as the Still piece. Francis D. Perkins once again had kind words for the commissioned works in his New York Herald Tribune review, saying that all three pieces were "engaging and instrumentally grateful." Eric Salzman, writing for the New York Times, was more specific about each piece, describing Aria as "mild, modal, [and] wandering.”14

Other noteworthy performances include (1) a May 6, 1962, Town Hall recital of exclusively A. A.A. works, including Aria, performed by Carrozza, which got glowing reviews from John Gruen of the New York Herald Tribune and from the New York Times;15 (2) a February 21, 1964, co-operative program of all-commissioned works by Cowell, Kleinsinger, Siegmeister, Bennett, Diamond, Luening, Creston, Brant, and, of course, Still, performed by four young and promising accordionists, Janice Simon, who played Aria, Joseph Soprani, Robert Conti, and Kathy Black, at New York's Donnell Library, which was broadcast over WNYC radio;16 and (3) another Carrozza recital, again including Aria, presented by the American Festival of Negro Arts at Aronow Hall, City College, New York City, on February 22, 1965.17

In addition to these and many other performances, Aria was included with other commissioned pieces in two A. A. A.- sponsored teacher/student workshops in New York on September 22, 1964, and September 27, 1969, and has been selected as the test piece for the A. A. A. national and regional competitions many times, as has Still's second accordion piece, Lilt, beginning at least as early as 1967. |

| |

|

14Francis D. Perkins, "Conductor-Composer Unit In Season's Final Concert," New York Herald Tribune, April 18, 1961, p. 19, cols. 1-2; Eric Salzman, "Brass Music Played by Composers Group," New York Times, April 18, 1961, p.42, cols. 3-4. Both this and the above-cited Chicago concert were also acknowledged in Pan Pipes of Sigma Alpha Iota 5412 (January 1962): 72. Regrettably, such major African-American newspapers and serials as the Chicago Defender, New York Amsterdam News, Jet, Ebony, and Black Digest, made no mention of any of the Still accordion performances.

15John Gruen, in "Week-End Events," New York Herald Tribune, May 7, 1962, p. 12, cols. 6-7; H. K., "Carrozza Presents Accordion Recital," New York Times, May 7, 1962, p. 39, col. 4. Unfortunately, neither review mentions Aria, owing partly to space given to the world premiere of Luening's Rondo in the same recital. The full program is given, however, in "Carmen Carrozza," Accordion and Guitar World 3013 (December 1965/January 1966): 8.

16[Elsie Bennett], "American Music Festival Features Accordion Works," A. A. A. typescript of press release, March 5, 1964 (in Bennett files).

17Announced in "Music Notes," New York Times, February 22, 1965, p. 14, col. 2, and recalled in "Composers Commissioning," by Elsie Bennett, Accordion Horizons 214 (Summer 1966): 13.

|

|

| |

(In fact, I recall that the first time I ever played Aria was as the required test piece for one of those contests in that period.)18

Besides these mostly New York programs, the celebrated, late Danish concert artist, Mogens Ellegard, played Aria and other A. A. A. works at the University of Miami's third annual Festival of American Music, May 4, 1962, and throughout Europe and Israel (including some radio and television broadcasts) in 1965. 19Back in the United States there were many other recitals and broadcasts that featured it outside of New York. Indeed, I, myself, performed the work - sometimes together with Lilt -- on at least six occasions between 1975 and today in recitals at St. John's College (Santa Fe, New Mexico), Johns Hopkins University, the Peabody Institute, Morgan State University (Baltimore), The College of New Jersey, and on a Morgan State University radio program on black music hosted by the well known authority on that subject, Dominique-Rene De Lerma. This performance history is probably fairly representative of that of many other concert accordionists regarding the inclusion of the Still pieces on their programs.20 |

| |

|

18For example, a September 14, 1968, letter from Bennett to Still indicates that both Aria and Lilt will be used as test pieces in different age groups for the Fall 1968 A. A. A. Eastern Cup Competition. Another letter, dated June 26, 1968, reports that Lilt was used as a required test piece in the sixteen-year-old division of the Fall 1967 A. A. A. Eastern Cup Competitions, and that the New York State Regional Competition also used it on May 5, 1968. Finally, Bennett tells Still in a letter of November 25, 1971, that "Aria is used at practically every contest that our [state] organizations have, and I am thrilled when I see it has been picked. Also, Lilt has been used." She goes on to write that Lilt was used in the November 1969 Eastern Cup Competition.

The workshops are reported in Bennett, "A.A. A. Seminar-Workshops Successful," Accordion Horizons: 1965 Convention Issue 1/4 (1965): 12, and "Robert Dumm to Analyze Sept. 27 Seminar," Accordion and Guitar World 29/4 (August/September 1969): 4.

19Review of Miami concert: Doris Reno, "Artist Tums Accordion Into a Concert Triumph," Miami Herald, May 5, 1962, p. 4-B, cols. 1-3 (I am indebted to Lynn Downing, at the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers, for this information). Ellegard undoubtedly played this work in many other programs in the United States and elsewhere, as did, certainly, numerous other artists not recorded here. News of the European and Israeli tour is relayed by Bennett to Still in a letter of February 21, 1965. Bennett had, in turn, heard about the tour in a letter received from Ellegard (Bennett files).

20Dates and locations of the McMahan performances: Garret Room of the Milton S. Eisenhower Library, Johns Hopkins University, April 25, 1975; Leakin Hall, Peabody Institute, May 11, 1975; Collegium Musicum program, St. John's College (Santa Fe, New Mexico), July 20, 1975; Murphy Auditorium, Morgan State University (Baltimore), November 3, 1977; Bray Recital Hall, Trenton State College (New Jersey), February 6, 1993; and "Melodies, Lyrics, and Notes," Dominique-Rene De Lerma, host, WEAA-FM broadcast (Morgan State University radio station), November 1977. None of these performances received reviews, although some concerts were mentioned in Accordion Arts Bulletin("Performances" [Summer/Fall 1975]: 6), Accordion Arts Magazine ("Performances," 1/2 [Winter 1978): 12), and a feature article on the writer in the Baltimore Evening Sun (Carl Schoettler, "Low Instrument Esteem Irks Accordion Virtuoso," April 17, 1975, p. B-1, cols. 1-6; port.). De Lerma sent a cassette recording of the radio program to the Stills (with a letter, dated October 25, 1977; copy in my possession), which (cont.) |

|

| |

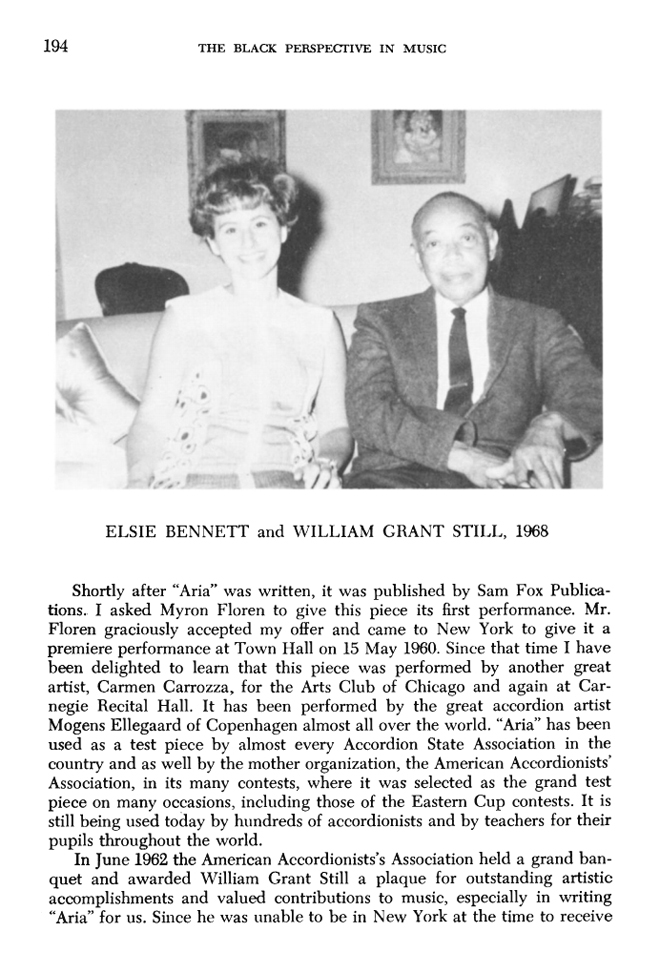

So grateful was the A. A. A. for this delightful little piece that Still was honored on June 25, 1962, at the Annual A. A. A. Dinner Dance, at the Commodore Hotel in New York. Unable to attend, he sent his good friend, the composer Kay Swift (perhaps most acclaimed for her 1930 Broadway hit, Fine and Dandy ), to receive a special plaque for him.

21 Later that summer, Ms. Bennett wrote in her article about him in the special May 1975 Festschrift issue of The Black Perspective in Music that she visited the Stills at their Victoria Avenue residence in Los Angeles, and they all became close friends.

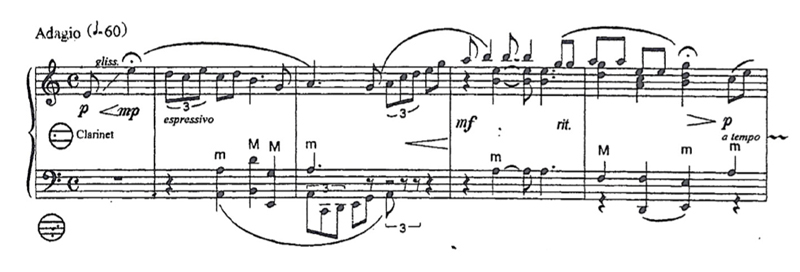

22 In an undated letter from Still to Bennett that must have been received sometime during early 1960, the composer describes the form of his piece as a rondo that breaks down into the following eight subdivisions (I have inserted the bracketed materials): |

| |

-

Theme I [measures 1-20; see Ex. la] I 2. Theme II (extended by development) [measures 21-30; see Ex. lb] I 3. Theme I [measures 31-38] I 4. Here a codetta takes the place of a transition [measures 39-42] I 5. Theme II (strongly contrasted and extended by development) [a tenuous connection,at very best; measures 43-94; see Ex. le]/ 6. Re-transition [measures 95-102] I 7. Theme I [somewhat altered; measures 103-18] I 8. Coda [based on Theme II; measures 118-24]23

|

|

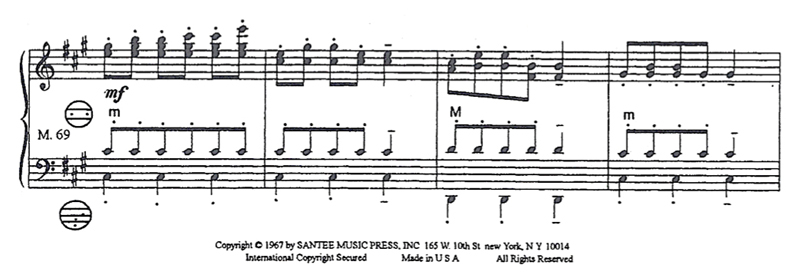

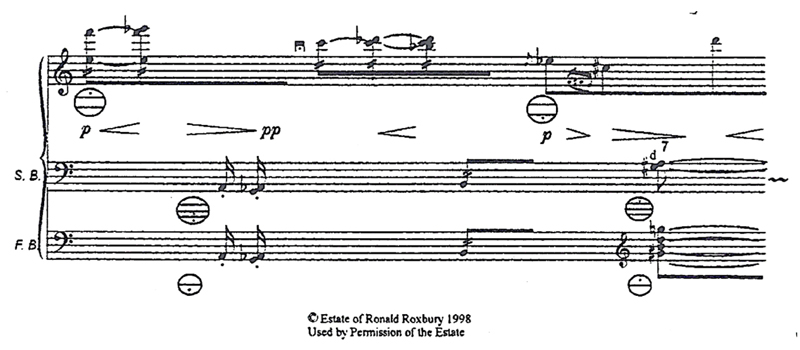

Example 1. Principal Themes from Aria, by William Grant Still |

(Note to non-accordionists: the chord symbols appearing over some bass notes, such as "M" [for major] , "m" [for minor], and "d"[for diminished], mean that the performer must play from those ready-made chord rows of buttons in the "Stradella," or "120-bass," left-handed manual; i.e., a single button will produce a three-note major, minor, incomplete major-minor 7th, or incomplete diminished-7th chord. Where two-note dyads appear, the chord symbol applies to the top note only. For example, in measure 1 of [a] below, the second beat of the left-hand part must be played as an A-minor triad [single button from the minor-chord row of buttons] against the lower single-note A available in either of the two single-note button rows [called "fundamental" and "counterbass," respectively] ; and the third beat would be played as a D-major chord button against a fundamental or counterbass, single-note B button, resulting in what is actually a B-minor 7th chord [B-D-F# -A].) |

| |

|

which would have joined earlier tapes they had received from Bennett of Ellegard and another unnamed artist (probably Carrozza) playing Aria (as mentioned in an August 21, 1962, letter from Still to Bennett [Bennett files]).

21Letter of invitation from Bennett to Still, June 11, 1962 (Bennett files); also mentioned in Bennett, "William Grant Still and the Accordion," The Black Perspective in Music 3/2 (May 1975): 193-95.

22Bennett, "William Grant Still and the Accordion," 95.

23[William Grant Still]: unpublished typescript, without date (Bennett files). |

|

| |

| a. Theme I, meas. 1-4 |

Years later, Still gave another description of Aria in a letter to Ms. Bennett. He wrote in the third person so that she could more fluently include it in a future article about him. As it turned out, the quotation was never used (although an accompanying one about Lilt was; see below). |

| |

The composer 's love for opera led him to write a broad, soaring melody reminiscent of operatic music. This appears at the beginning and end of Aria, the sections separated by a Scherzo-like movement demanding nimble fingers and a clear sense of rhythm. The piece employs many of the unique resources typical of the accordion as an instrument.24 |

|

| |

|

24Letter from Still to Bennett, June 23, 1968 (Bennett files). In her letter to Still (June 20, 1968 [Bennett files]) preceding this reply, Bennett asked for his descriptions of both Lilt, which he had recently completed, and Aria for her upcoming article announcing the completion and publication of the former. |

|

| |

The piece may be more readily perceived as a large A/B/A' scheme, however, because Still's designated items 1 through 4 seem to be all of one fabric, owing to the slow but rather rubato tempo and a fairly faithful adherence to the Aeolian mode in the main double-period portion of the principal theme; item 5 (the "Scherzo-like movement" mentioned in the second quotation above) is in a sprightly, faster tempo, and a considerably chromaticized but clear F major, and presents a strong contrast to what came before despite its disguised derivation from the earlier "Theme II"; and, following the bluesy, slow retransition (section 6), there is a truncated, but nonetheless lengthy, return of the opening section's main theme and, very importantly, slow tempo and A-minor tonality, prior to the dramatic coda.

The mood of the entire work is very peaceful and poetically fragile, with characteristically Stillian touches of modal and pentatonic writing moderately imposed upon an otherwise frankly tonal and post-romantic style. Though the finger work of Aria is easily rivaled by the virtuosic requirements of such other A. A. A. commissions as the Creston Concerto and Krenek Toccata,25 I have played few pieces that make as high a demand on the performer's expressive abilities - and expose performance mistakes so clearly! It nevertheless comes quite close to what Ms. Bennett requested of Still in her first letter of invitation for a commission, some six months before the official contract was sent: |

We would like something ranging from medium to difficult to perform since we would like the number to be featured on concert programs. If the number were suitable it might also be used by contestants in our various accordion contests. This is not a prime consideration, however; we are more interested in getting a good piece of music that has something to say.26 |

| |

|

In this same letter, Still was offered the usual A. A. A. remittance of $200, to be paid jointly by the A. A. A. and his publisher.

Typical of many of the A. A. A. commissions of the 1950s, 60s, and early 70s, Aria calls for the traditional piano accordion with the standard, so called "Stradella" ("120-bass") left-hand manual, consisting of one octave of single notes (extendable to other octaves by means of registral switch changes), and preset major, minor, major-minor seventh, and diminished chord buttons (see Example 1). The chord buttons, often condemned by music purists, nevertheless allow composers to come up with some very inventive polytonal or tone cluster structures, often performed at high speeds, which are difficult or impossible to obtain on other keyboard instruments. |

| |

|

25Creston's Concerto for Accordion and Orchestra or Band, Op. 75, was the third commission by the A. A. A. (1959) and was published by Ricordi in 1960. Krenek's Toccata, Op. 183, was the twentieth commission (1962) and was published by 0. Pagani in 1964. I recorded the Toccata on Orion Records (Ernst Krenek, ORS 75204) in 1974 and assisted the composer in writing his second accordion piece, Acco-musik, in 1976.

26Letter from Bennett to Still, May 27, 1959 (Bennett files) |

|

| |

Many later A. A. A. works allow the performer to use the more recently invented three to four-octave single-note arrangement of the "free bass" manual, which is available in two different formats, one of which is chromatically arranged and the other following the circle-of-fifths layout of the Stradella system. (Most classical accordionists have instruments in which the free bass coexists with the Stradella in a larger, heavier left-hand section.)

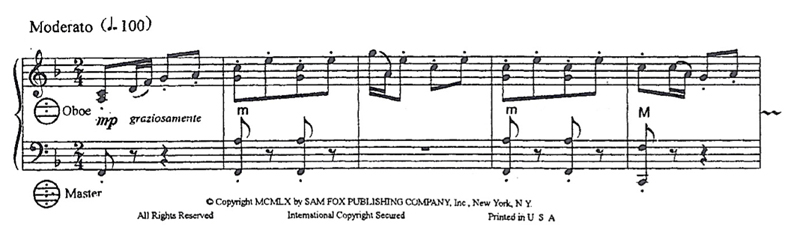

In a feature article on Still in the November 1963 issue of The Music Journal, we find him still saying good things about the accordion: ". . . I know this instrument has wonderful possibilities and there are always fine accordionists who would like to see more music composed specifically for their instrument."27 Elsie Bennett and the A. A. A. eventually followed up on this notion by asking Still to write another accordion solo. The expressed goal of this commission, as stated in a letter from Ms. Bennett to the composer dated February 21, 1965, was "to write a simple piece that could be used for teaching purposes."28 The contract was sent to Still the following summer, on July 5, 1966, and the resulting piece, indeed easier technically, but, typically, not expressively, was entitled Lilt. It joins other intermediate level student commissions, such as Jose Serebrier's Danza Ritual, Creston's Embryo Suite, and Tcherepnin's Zigane, all commissioned around the same time.29 According to A. A. A. contract records, it constitutes that organization's twenty-ninth commission.

An article in the Fall 1968 Accordion Horizons magazine announced the publication of Lilt by Pietro Deiro Music (a longstanding accordion publisher, no longer extant) and the fact that it had been chosen as a test piece for both the A. A. A. Eastern Cup and New York State regional competitions that year (see note 18). In addition, Still is quoted as describing his new piece as a "jaunty, good-humored little tune with an easy, infectious rhythm. The middle section, also melodic, offers a sparkling contrast to the basic theme."30 (But the rather brief middle section is not as strongly contrasted to the outer A sections, at least with respect to tempo, as are the principal segments of Aria to each other.)

Like Aria, Lilt is written for the standard piano/Stradella accordion. It is similarly serene and tonal (A-major/A-minor/ A-major with the usual modal and pentatonic leanings), and follows a similar rondo plan, framed

|

| |

|

27Joyce Lippy and Walden E. Muns, "William Grant Still," Music Journal 21/8 (November 1963): 34, 70.

28 In Bennett files.

29Serebrier's Danza Ritual is either the twenty-seventh or twenty-eighth commission (contracted on the same date as David Diamond's Introduction and Dance, March 17, 1966), and was published by O. Pagani in 1967. Tcherepnin's Zigane (1967) and Creston's Embryo Suite, Op. 96 (1968), were the thirty-first and thirty-second commissions, respectively. Both were published in 1968 by Pietro Deiro.

30Still's description, which accompanied his analysis of Aria, appears in both the undated letter to Bennett cited in note 23 and Bennett's unsigned article "William Grant Still Writes Second Work for Accordion," Accordion Horizons 414 (Fall 1968): I I. |

|

| |

within larger A/B/A sections (see the synopsis in Ex. 2). And, as may be expected in a composition intended for students, it is melodically, harmonically, and formally simpler and more "popular" in nature than is its lengthier and more serious predecessor. |

| |

Example 2. Synopsis of Lilt, by William Grant Still. |

| |

Rondo form within larger A-B-A format.

A section, minor/modal quality; meas. 1-60: Introduction, meas 1-8, A-dorian mode |

Return Theme III, extended and ending on half cadence (inverted dominant-11th chord [B-D-E-A]); meas. 77-86.

Return A Section, truncated, original key; meas. 87-14.

Return Theme I, expanded, A-aeolian mode; meas 87-102

Return Codetta, expanded, varied; material from Introduction and Theme I; meas. 103-14; cadence on A-minor tonic.

Curiously, to judge from the chronological list of works in William Grant Still and the Fusion of Cultures in American Music, both accordion pieces were written at times of seeming inactivity for the composer. It appears that Lilt was the only work completed in 1966; and Aria, along with the orchestral tone poem Patterns and the "Lyric" string quartet, all purportedly completed near or during 1960, followed the Third Symphony and the opera Minette Fontaine by a year, with nothing showing for the bulk of 1959. The years between 1960 and 1966 are furiously busy, however, with at least sixteen works listed in the chronology, including the opera Highway 1, U. S. A., the orchestral works Los Alnados de Espana, Preludes, and Threnody: In Memory of Jan Sibelius, the Folk Suites, Nos. 1-4, for various chamber ensembles, and Still's only two works for organ.31

It is remarkable to observe that William Grant Still is apparently the only published African-American composer to have written concert music for the accordion to date. It must be added, though, that Ulysses Kay accepted a commission from the A. A. A., dated November 24, 1961, but that, regrettably, he soon returned his contract to Ms. Bennett, explaining that he had tried but felt that he could not succeed in writing something fitting for the instrument.32

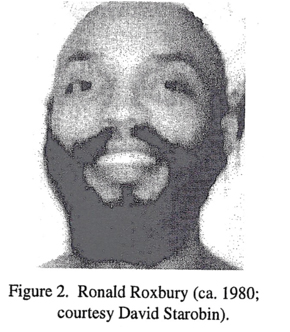

Not shrinking from the challenge of writing for this unfamiliar new medium, however, was a former classmate of mine at the Peabody Institute, Ronald Roxbury. Roxbury was a refreshingly whimsical, often outrageous, and uniquely talented African-American who, as the oldest of six musically inclined children of Carroll and Rachel Roxbury, grew up in Fruitland, Maryland, near Salisbury and the famous "Eastern Shore" of the Chesapeake Bay. He was drum major at Salisbury High School, could play almost any instrument (though flute was his principal choice), and possessed an unusual counter-tenor voice, which he used frequently in his career.33 Roxbury came to Peabody in 1964 and was a composition and theory student of Stefans Grové (the Institute's most sought-after instructor of those subjects at the time; he returned to his native South Africa to teach at the University of Cape Town in the early 1970s). He remained in Baltimore into the early 1970s, earning bachelor's and master's degrees in composition. During his graduate years, he and two other colleagues,

|

|

31Celeste Anne Headlee, "Thematic Catalog of Works (1921-1972)," in William Grant Still and the Fusion of Cultures in American Music, 2nd ed., Judith Anne Still, ed. (Flagstaff, AZ: The Master-Player Library, 1995), 229-30, 252-59, 267-69, 271-73, 275-76, 285-87, 296-97, 299. Partially supporting this statement, Still's wife, Verna Arvey, wrote in her book about "Billy" and herself that the Serenade for Orchestra and "two subsequent commissions by the American Accordionists' Association were the only [works] completed during this period" (Verna Arvey, In One Lifetime [Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1984], 174). Ms. Arvey's account, which gives no exact parameter of years, is considerably inaccurate, however, though Headlee indicates that the Serenade was completed in 1957 and merely premiered in May, 1958 (p. 252), and that Aria was completed by early 1960. Lilt, as has been shown above, was not commissioned and composed for another six years

32Bennett files.

33Telephone interview with Roxbury’s mother, Rachel Roxbury, June 20, 1998. |

| |

composer Willam Bland (who was also briefly on the Peabody theory faculty from about 1970to 1972) and clarinetist/composer Steve McComas, joined the now renowned guitarist David Starobin to create a New Music ensemble dedicated to the performance of aleatoric and improvisatory works by such noted avant-garde figures as Earle Brown (who was in residence at Peabody during this period), Karlheinz Stockhausen, and John Cage, in addition to, of course, Roxbury.

In 1973, he struck out for New York and was soon joined by Starobin and two other former Peabody classmates, baritone Pat Mason and pianist/poet/composer Rick Myers. Forming a new contemporary ensemble similar to the old one in Baltimore, they free-lanced around New York.34During those last twelve or so years of his all-too-brief career, he performed with both the Philip Glass Ensemble (he is in the chorus on the CBS 1984 LP of Einstein on the Beach),35 the Meredith Monk Vocal Ensemble, and toured Europe with Eric Salzman's QUOG ensemble (in which he performed with the noted New York accordionist William Schimmel, who introduced him into that group as well as indirectly into those of Glass and Monk).36

At about the same time Still's Lilt was published, Roxbury, while still an undergraduate at Peabody, wrote an excellent and highly idiomatic set of four atonal Preludes for accordion for another accordionist and mutual friend at the Conservatory, Charles Raymond Bitzel (1946-76). A native of the Baltimore area, Bitzel was an oboe and education major who, outside Peabody, had been a student of an important older-generation artist, Frederick Tedesco, whose studio was only a few blocks from the Institute. I had the pleasure of premiering that composition at Roxbury's bachelor-degree recital in the Peabody Concert Hall, on March 26, 1968, and can happily report that the A. A. A. is currently looking into having it posthumously commissioned and published.37Later on, during his New York years, Roxbury had promised to write two more accordion works,

|

| |

|

34David Starobin, "Ronald Roxbury: A Remembrance," Guitar Review 66 (Summer 1986): 23.

35Philip Glass, Robert Wilson, Einstein on the Beach; Philip Glass Ensemble, CBS M4K38875 (1984). Roxbury is listed in the chorus and is partially visible in one of the photographs in the accompanying thirty-three-page booklet and libretto

36Interview with William Schimmel, November 25, 1998. Schimmel also noted that a 1975 performance by QUOG at Cirque de la Mama, in New York, attracted both Glass and Monk. Upon experiencing Roxbury's unusual singing and theatrics, they both sought his services in their ensembles.

37Ronald Roxbury, Four Preludes for Accordion (1968). The original MS of this work was long in the possession of William Schimmel who gave it to me in 1995; I donated it to the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, where it is included in the Ronald Roxbury Papers, housed in the Peabody Music Library Archives. With respect to Roxbury's degree recital: Bitzel was unable to perform the Preludes at the time, and Roxbury therefore asked me to play them instead. |

|

| |

this time for Schimmel: a concerto for accordion and strings and a duet for accordion and guitar;38 unfortunately, they never materialized, owing to the composer's untimely death at forty, on March 22, 1986.39

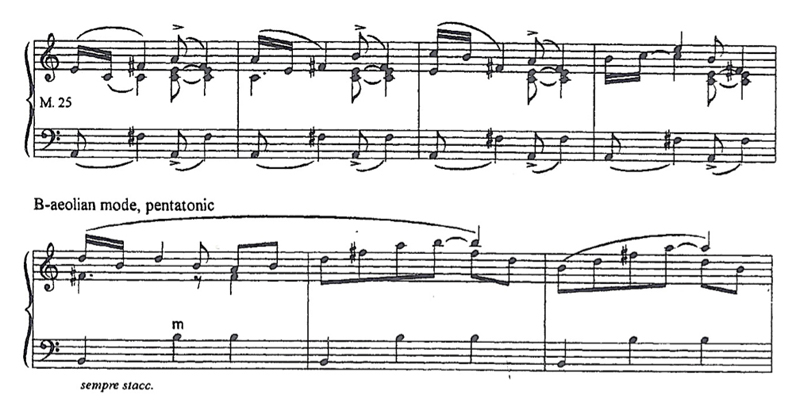

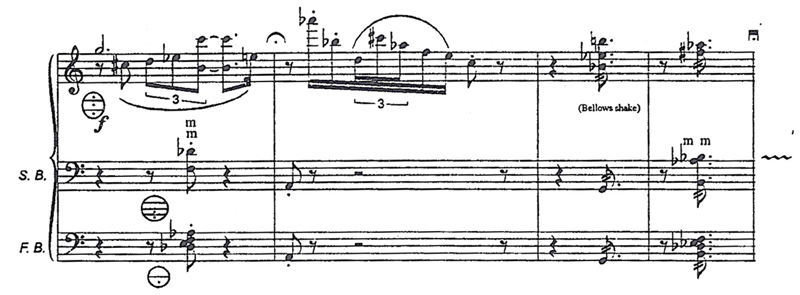

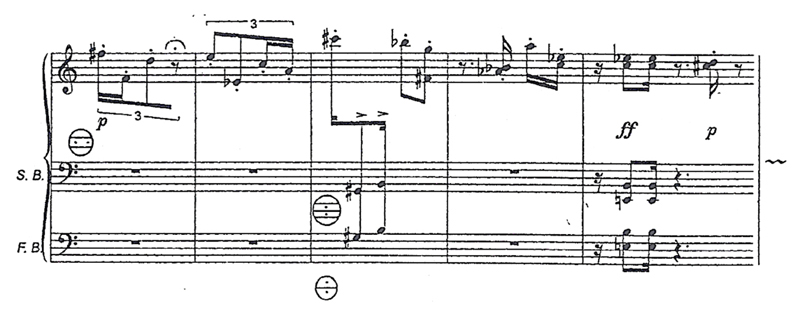

The Four Preludes consists of that many short, highly contrasted vignettes in classic 1960s-era free atonal, freely measured style (see Example 3 for the opening measures of each). The tempo scheme is slow ("Very slow"), moderate ("Allegro, ma non troppo"), fast ("Very fast,

always dizzy"), slow ("Desolate [freely]"). The first and fourth Preludes are the most mysterious and nebulous of the set. This is particularly true of the latter, which is indeed "desolate" and removed, owing to its scattered high bellows shakes, interspersed with short moments of more lucid melodic "contact" with the listener; it is as if it is being received from outer space through a faulty transmitter. By contrast, the predominately staccato, "pointalistic" second Prelude is comically rigid and eccentrically militaristic, while the third is a moto perpetuo, whose rapid, "dizzy" triplet-figure flights are briefly interrupted twice by lethargic, brooding moans deep in the bass.

|

| |

|

Example 3. Opening excerpts from Four Preludes, for accordion, by Ronald Roxbury. I have added an optional/alternate part for Free Bass (third staff in each system) to the original Stradella Bass part (second staff). |

|

| |

| 1. Very Slow Recording by Robert McMahan: Link to 1st Movement |

| |

Roxbury takes full advantage of the instrument's unique idiomatic and virtuosic qualities in all four segments. In general, he favors the more contrasted and pure sounding single or double-unison ranked right-hand registers (such as "Piccolo," "Clarinet," "Violin," and "Bassoon"), though he is not afraid of occasionally opening up to the fuller quadruple-and triple-ranked stops of "Master" and "Harmonium" for more dramatic moments. The virtuosic demands on the performer range from the unusual simultaneous bellows shake and right-hand trills in the first movement (which he once said reminded him of radio interference; not shown in the example), as well as more commonplace employment of bellows shake alone elsewhere in that movement and throughout the last, to the blindingly rapid third movement, which culminates in flying double notes(not eased by the less responsive "Bassoon" register employed there) that would be virtually unplayable on the stiffer action and wider keys of the piano. Like Still, Roxbury wrote the Preludes for the standard 120-bass accordion. I have, however, taken the liberty of appending a Free-Bass alternative (marked "F. B." on the third staff of each excerpt in Ex. 3) to the original left-hand part (marked "S. B.," for "Stradella Bass," on the second staff of each system) for a cleaner sound and more even balance with the right-hand part. The performer may, of course, choose the system that he/she finds most comfortable or appealing.

Though Roxbury's capricious personality and adventurous experimentalism are strongly stamped on the accordion pieces, they are considerably tight and conservative when compared to the highly aleatoric, graphically notated, theatrical, multi-medea, and often intentionally absurd music 'he produced in the years after 1968. A representative list will easily demonstrate these descriptions: Gazelles (1969), which requires a belly dancer; Grenades, or Several Bags of the Abominable Snowman, for flute, guitar, and contrabass (1969); two theatre pieces, Afternoon of an Evening and Apotheosis and Dirge in E-flat (produced by Foster Grimm in Baltimore, 1973-76); Le Sofa de Solfeges, for soprano in Jean Harlow wig and feather boa, reclining on a nineteenth-century sofa, with guitarist obliviously playing exercises (1974); Leda and the Velvet Gentleman (chamber opera, ca. 1974; recorded by Gregg Smith); and Four Driscoll Songs, for baritone, guitar, and water obligato (1975).40

It should be clear from all of this that the musical leanings of the radically chic Roxbury and his older, distinguished fellow-African American counterpart, the post-Romantic William Grant Still, who drew so often from his generational heritage of spirituals and jazz, represent a strong polarity. It is probable that the two would have carried on quite a lively debate over the comparative merits of the diverse musical languages of our century had they ever met (though I personally remember Roxbury as one who, while often seeming irreverent towards

|

| |

|

40David Starobin, "Ronald Roxbury: A Remembrance," 23. Leda and the Velvet Gentleman is recorded on Grenadilla Records. For Four Driscoll Songs, see review in Donal Henahan, "Music: 'Legacy' Pieces,'' New York Times, July 31, 1975, 34: 1-2. Also reviewed there is a work by William Bland and performances by Starobin, Patrick Mason, and Bland. A number of Roxbury's highly graphic scores may be viewed in his papers at the Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University Music Library Archives. |

|

| |

past practices and existing societal sanctions, was never outwardly judgmental of others or their ways). In any event, from the vantage point of practically forty years since the first of the accordion works discussed was composed, there is no doubt that, despite the wide chasm that separated their two musical worlds, both men contributed delightful and very significant little gems to the accordion's growing serious repertoire. This is attested in part by my recent and very pleasurable experience of performing and speaking about their accordion music at the 1998 conference "William Grant Still and His World: A Celebration of Cultural Diversity" at Northern Arizona University, at Flagstaff. The sizeable audience, largely African American, but by no means exclusively so, was absolutely delighted with all three selections. Not long afterwards, one listener, an African-American composer and university professor, wrote to me in order to seek assistance in composing something for the accordion. Hopefully, that was a sign that this article will have to be updated before long to include many more of that regrettably under-represented group of composers who have written serious works for the accordion.

|

| |

| ****** |

I should like to thank Elsie Bennett and Stanley Darrow for generously opening their extensive accordion archives to me for hours and days on end and for their invaluable and unrestrained assistance in many other ways. |

| |

|

| |

In her ongoing efforts to make the general music public outside of the accordion world aware of the instrument’s growing contemporary original classical repertoire, Elsie Bennett was able to have an article she wrote on the two AAA Still pieces published in the May 1975 issue of the highly respected, peer-reviewed scholarly journal The Black Perspectives in Music. It appears below for the interested reader. As will be obvious to readers of my articles on the Still works for the AAA Festival Journal, Free Reed Journal, and this website series, it was among the sources from which I drew much of my information. This particular issue of TBPIM was dedicated to Still in celebration of his eightieth birthday and includes several other articles on his works and life in addition to that by Bennett.

RYM |

| |

|

| |