|

| As Chair of the AAA Composers' Commissioning Committee, I have been writing articles the AAA Music Commissions through the decades. A short history of the Committee is online.

|

Dr. Robert Young McMahan |

Composers Commissioning Committee: |

The year 1964 witnessed three successful commissions by the AAA Composers Commissioning Committee. In order of dated contracts, they were Normand Lockwoods’ Sonata Fantasy (discussed in article 13 in last year’s AAA Festival Journal), Nicholas Flagello’s Introduction and Scherzo, the subject of this writing, and the third of four commissions by Paul Creston, Fantasy, for accordion and orchestra or, as specified by the composer, solo accordion (to be discussed in the next article). Nicholas Oreste Flagello was a life-long New Yorker from his birth in that city on March 15, 1928, to his death in New Rochelle in 1994, a day after his 66th birthday. In addition to being a composer, he was a conductor and pianist, who studied composition with Vittorio Giannini and conducting with Jonel Perlea at the Manhattan School of Music, where he received his MM in 1950. He also received the Diploma di studi superiori in 1956 from the Accademia di S Cecilia, in Rome. He was professor of composition and conducting at his alma mater from 1950 to 1977, and was an active conductor and pianist for that whole period, having made many recordings conducting the Rome Symphony Orchestra and Rome Chamber Orchestra. A full-page feature article on Flagello and his commission by AAA Composers Commissioning Committee Chair Elsie Bennett appeared in the January 1971 issue of the Music Journal. In it, Bennett explained that her son Ronald was a student at the Manhattan School of Music in 1958 and he expressed great admiration for one of his professors, Flagello. This led her to show Flagello the score of what was only the second AAA commissioned work at that point, Cooper Square, by Wallingford Riegger (discussed in one of the earliest articles in this series). Rather than just flipping through the music, Flagello spent almost an hour studying it closely and “discussing the pros and cons he saw in relation to Riegger’s other work”. (Cooper Square was in a kind of abstract popular style with Latin rhythms—a far cry from his usual dissonant and sometimes atonal writing— and perhaps disappointing to some at the time who were expecting something more daring for the accordion’s fledgling modern repertoire.) Eight years later, in 1964, Art Guerrero, then a student of Flagello’s at the Manhattan School of Music and an acquaintance, and possibly an accordion student, of Elsie Bennett, informed her that Flagello might be willing to write for the accordion. Consequently, Bennett offered Flagello a contract to write a solo piece for the AAA in a letter dated March 20, 1964. In the letter she also reminded him of the meeting they had together "a few years ago." The composer responded in the affirmative, asking for a registration chart and the loan of an accordion (which Guerrero delivered to him soon thereafter). The two also agreed on a deadline of June 20, exactly three months away, which was met. |

|

Nicholas Flagello and Elsie Bennett, June 17, 1960. Elsie Bennett photo album. |

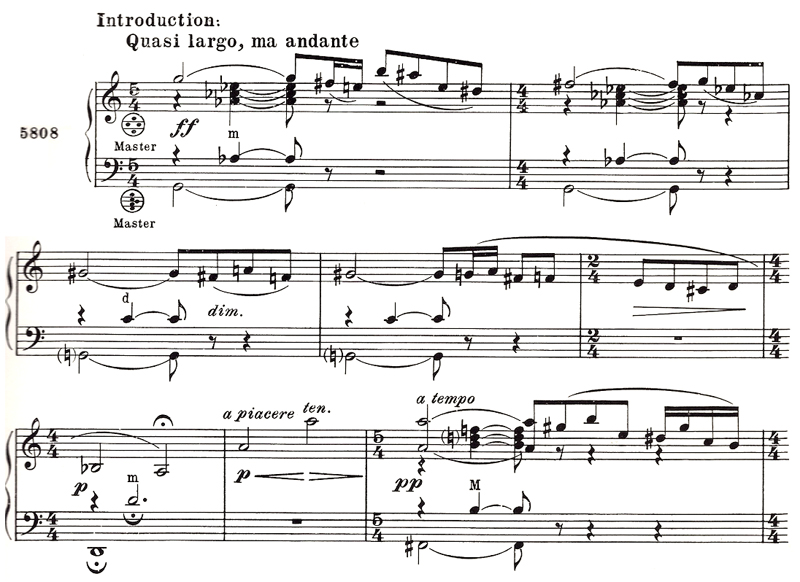

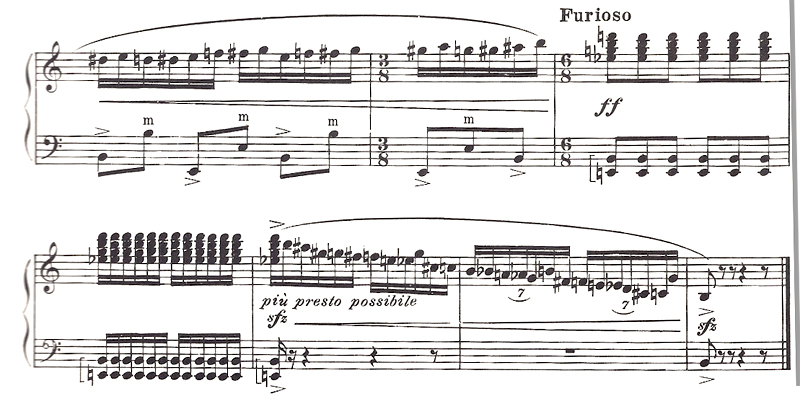

Flagello's music has a flare for the dramatic, which may explain his creation of six operas and numerous songs and choral works across his career. It should therefore also not be too surprising that his brother Ezio was a basso with the Metropolitan Opera at that time. Nicholas was nevertheless just as prolific in his orchestral and chamber music output as he was in his music for the stage. In an era when atonal and serial music was most in vogue, Flagello, like his teacher Vittorio Giannini, wrote in a post-Romantic language. However, beginning with such mid-career works as his fifth opera, The Judgment of St. Francis (1959; premiered in New York, 1966), his harmony became somewhat more dissonant, though mainly via extended tertian structures commonly heard in jazz and film noir motion pictures, his rhythm more complex, and his musical expression more emotionally intense and even angry at times. Nonetheless, his music did not gain the attention in the closing decades of the century that more objective ears today would possibly be giving it along with the works of such other "outdated", non-atonal composers commissioned by the AAA then as Creston, Kleinsinger, Siegmeister, Still, Surinach, Tcherepnin, and Thomson. The Introduction and Scherzo falls right into the midst of that time and is a perfect example of this more advanced stage of Flagello’s musical evolution. From its stormy beginning to its almost despairing, tragic end, the Introduction and Scherzo has very few moments of rest and calm for either the audience or the performer and is intensely serious in nature. In that sense, it is indeed very operatic, and its ethos might especially be compared to that of the gritty, "verismatic" operas of Leoncavallo and Mascagni at the beginning of the twentieth century. For the accordionist, this is a very "athletic" and unrelentingly forceful piece that demands of the instrument and performer a healthy set of bellows and a strong left arm! The composer himself stated in the above article that it is "a very difficult piece" and that it is "written to show off the virtuosity of the instrument just as all other music has been written for all the other instruments in the past." The article also reported that Flagello assured Bennett that he would write his "best music" for the accordion and opined that "some composers think they are above writing for the accordion. But you don’t restrict anybody; if he is a good composer, he can write a good piece." As its title infers, the Introduction and Scherzo falls into two major sections: A brooding Introduction (marked Quasi largo, ma andante) of 37 measures and a longer, 98-measure, but faster, waltz-like Scherzo (Allegro, ma incominicando lento), predominately in 6/8 meter. It is a very well crafted, tightly composed work that, due to its unrelentingly violent, melodramatic, bombastic nature and dissonant but standard extended tertian harmonies, some would call "way out" or extremely modern. However, it is actually more traditional in style than the novice to "New Music" might think. As with much "neoclassical", conservative twentieth century music of this sort, there is also a hint of a key (what in modern music is referred to as "centrist" music, suggesting an abstract nod to 19th century and earlier "tonal" music), particularly in the Scherzo, which seems to be in the key of E minor in the beginning but ends on a strong B tonic note at the closing bar. The Introduction divides into two main segments. The first consists of fluctuating meters of 5/4, 2/4, and 4/4 in the intrusive declamatory opening of dramatic, often rapid falling figures, made more melodramatic by frequent film noir-type harmonies, such as the minor/major 7th chord in the first and second measure (A-flat – C-flat – E-flat – G, further dissonated by an Fsharp in the second measure), and the highly dissonant polychord of B major-minor 7 (B – Dsharp – F-sharp – A) versus B half diminished 7 (B – D – F – A) in the new phrase beginning at measure 8. The opening segment is nevertheless "resolved" at measure 6 on a D-minor triad, serving as a would-be tonic chord, at least temporarily. Similar weavings inside and outside of dissonant and consonant harmony will persevere throughout the piece. |

This opening is followed by a more metrically consistent and longer section in 6/8 time that, by fits and starts at first, eventually rushes towards the Scherzo, often carrying prophetic hints of the main motive of that section, an upward moving arpeggio of a major 7th chord. After collapsing into a morose low point in the right-hand range, the Introduction ends in what might be construed as a kind of conquered acceptance of some kind of inevitable fate. This effect is achieved via repetitive, unresolved, though anchoring, C-sharp minor triads to which is soon added the tense effect of G augmented triads superimposed upon persistent, but now hollow sounding, C-sharp/G-sharp dyads serving as focal pedal points in the bass. In continuing to prepare the listener for the equally fretful Scherzo, the melodic line drops even lower before moving attacca into that more persistently rhythmic movement, marked "Allegro (ma incominciando lento)." The translation is literally "Cheerful, but starting out slow," though it seems that the more general notion of just "fast" for "allegro"is more appropriate for this Scherzo since it is anything but cheerful due to its driving, urgent, brooding nature. Even the generic title of this segment, "scherzo," seems a bit out of character since its literal translation is "joke." Once again, one could take the notion that scherzo here possibly suggests more of a sardonic laughing at fate rather than something light and playful (even if a bit mischievous or devilish). |

| The Scherzo is in a roughly A-B-A1 tripartite form. The aforementioned Allegro, bearing and developing the upward moving arpeggio motive, constitutes the A section. |

| After many dynamic rises and falls and at times technically daunting, roller-coaster-like runs, the music plummets downward to a subsection of brooding utterances. These soon erupt into hammering repeated dissonant chords that climb ever upwards to a climatic dissonant chord beginning the brief B section, marked Andante. |

| The Andante’s dissonant outcries soon collapse into a brief chordal Lento segment offering slight relief from all the foregoing strife and gradually preparing the listener for the return of the Allegro (A1). |

| The first twenty measures of the initial Allegro are now repeated verbatim in its return. This then leads into a lengthy coda that climaxes in a final five-measure segment ("Furioso") carrying violent, hammering repeated E-flat augmented/major 7th chords in the treble that are strongly dissonated by supporting E-natural/B-natural dyads in the bass before the right hand spirals downward via an urgently rapid, highly jagged and chromatic line to a finalizing single note B. |

| The Introduction and Scherzo has had a very busy performance life. Practically every American accordion student competing in the AAA competitions of the 1960s has played it either as a required test piece or an elective in the Original Virtuoso division of the 1960s. In perusing the archived Bennett correspondence the writer himself was reminded by a November 1968 letter from Bennett to the composer that he took second place in that division with the Introduction and Scherzo in that year’s national competitions. It was also a test piece for the 1965 CIA Coupe Mondiale in which Beverly Roberts made history by becoming the first female American international winner. Most recently, it was one of the choice test pieces a few years ago in the Carrozza Scholarship Division of the AAA Festival in Alexandria, Virginia. It has also been recorded at least once by Frank Hodnicki on Kaibala Records some time before 1971 (Original Music for Accordion: No. 2). |

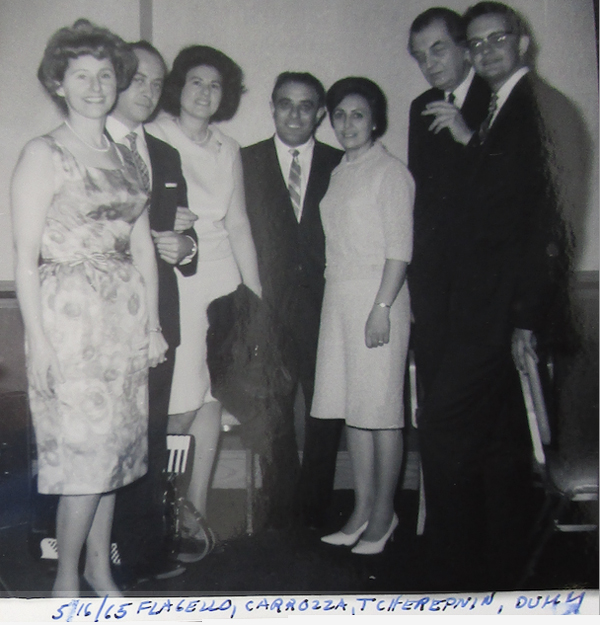

Elsie Bennett, Mr. & Mrs. Nicholas Flagello, Mr. & Mrs. Carmen Carrozza, Alexander Tcherepnin, and Prof. Robert Dumm, AAA CCC Workshop, New York, May 16, 1965. Elsie Bennett photo album |

|||

| In addition to its accordion history, it was recently brought to the writer’s attention by the eminent classical saxophonist Paul Cohen that the Introduction and Scherzo went through a curious and unexpected second incarnation. This was due to the inspiration of musicologist and colleague of Flagello, Walter L. Simmons, who has recounted the event on the To the Fore Publishers website (see www.totheforepublishers.com/noire.html), partially quoted here: | |||

|

This is not the only time an AAA commissioned work has been transcribed to another medium. William Schimmel once transcribed Luening’s Rondo for string orchestra; and more recently, Robert Baksa transcribed his Sonata for Accordion (1997) two ways, one for two pianos and another for organ. There was a plan to once again resurrect the Introduction and Scherzo either later in 2011 or in 2012 in a joint concert of works for saxophone, accordion, accordion and saxophone, and saxophone quartet, performed by Paul Cohen, the writer, and others. In addition to a new work by the writer for soprano saxophone and accordion (Romp II) as well as his Three Sets for Saxophone Quartet (2010), both the original accordion version and the saxophone quartet rendering (again, retitled Valse Noire) would have been on the program. Unfortunately, plans fell through for this event. However, one can hear the writer’s Romp II and Three Sets, for Saxophone Quartet on Youtube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8y0FDQVHGPI and Viva Introduction and Scherzo! |

Performances by Carmen Carrozza and Mario Muccittoo of Introducton and Scherzo may be

heard in the AAA listing of commissioned works at Other concerts of AAA commissions and other contemporary works performed in 2011: Dr. McMahan performed the solo version of Paul Creston’s Fantasy, for accordion and orchestra or solo accordion, the AAA commission that followed that of Flagello's Introduction and Scherzo, at the AAA Master Class and Concert Series, Tenri Institute, New York City, July 29-31, 2011. He also premiered his Romp II, for soprano saxophone and accordion, Paul Cohen, saxophonist, at that event (which is recorded on the above referenced Youtube video). |