Music Commissions Home | Music Commissions Brief History | Music Commissions Articles List | Composer's Guide to the Piano Accordion

In 1962, Elsie Bennett was able to successfully commission, or in two cases, recommission, four of America's most celebrated composers, David Diamond (Sonatina), George Kleinsinger (Prelude and Sarabande), Ernst Krenek (Toccata), and Robert Russell Bennett (Quintet for Accordion and String Quartet ["Psychiatry"]). As mentioned in the 2005 article of this series, she also commissioned the Hollywood film composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, who unfortunately died before he could realize the project. In this issue, we will concentrate on the second piece of 1962, having already discussed the first (Diamond's Sonatina) in the previous issue of the AAA Festival Journal: Kleinsinger's Prelude and Sarabande, for solo accordion, contracted on January 18.

George Kleinsinger (born 1914 in San Bernardino, California, died 1982 in New York City) will always be remembered for his very popular "melodrama" for narrator and orchestra entitled Tubby the Tuba (1942), the story of a tuba that tired of being limited to "oom-pah-pah" parts in the orchestra (this should strike an empathetic chord among accordionists!) and that aspired to play soaring melodic lines. It immediately won a permanent place in children's symphonic concerts and was even made into an animated cartoon by Paramount Pictures, earning the composer a nomination for an Oscar. Though known for his eccentric personality, Kleinsinger was no musical radical, preferring to write in an essentially tonal and highly melodic style. The Prelude and Sarabande proved to be no exception, as will be demonstrated below.

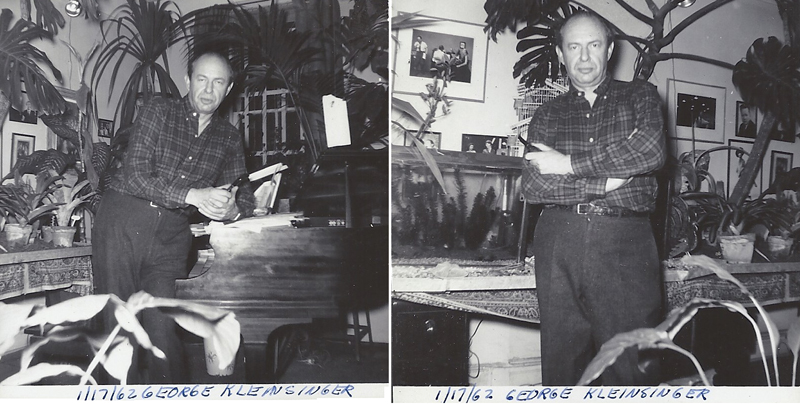

Notes in Elsie Bennett's archive report that she first met Kleinsinger on January 17, 1962, at his unusually furnished studio apartment in lower Manhattan's infamous Chelsea Hotel, noted since its first tenants inhabited it in 1884, as the abode of numerous celebrated and equally eccentric composers, artists, writers, and thinkers, including another odd AAA commissionee, long-time resident Virgil Thomson. As conservative a composer Kleinsinger was, his notion of an ideal living environment would have to be deemed radical by all estimates. Upon moving into the Chelsea, he converted it into a virtual ecosystem, described by one visiting reporter as follows:

| Part of the studio floor is . . . covered with tin and turned up at the edges to form a huge irregular tray covered with dirt, sand, rocks, grass and tropical plants in which a three-foot iguana, a python, a blue racer and leopard-turtle theoretically reside . . .Tubs of rare 12-foot palms from Borneo and Madagascar dot the room. In these, Brazilian cardinals, finches and colorful toucan perch or fly about the room. A large caged African bird accompanies Kleinsinger in a raucous voice when he plays the piano. Kleinsinger's wife no longer lives with him. "She got used to the snakes, but she couldn't stand the birds," he said.* |

|

Bennett visited Kleinsinger a second time a month later, on February 14. At their first meeting Kleinsinger had pledged to Bennett that he would have the piece completed by his birthday, on February 13, which he apparently succeeded in doing, and handed his score over to Bennett.

Kleinsinger was no stranger to the accordion, having used it in many of his movie and television scores, and once considering employing it as the sole accompanimental instrument for his chamber opera Shinbone Alley (he ended up using a jazz combo instead). He told Bennett that he was sympathetic towards "neglected" instruments and often featured them in his compositions. For example, in addition to Tubby the Tuba, he wrote another orchestral narration, this time for the piccolo (Pee Wee, the Piccolo) and a concerto for harmonica (Street Corner Concerto for Harmonica, commissioned by harmonicist John Sebastian in 1947). He admired the accordion for a number of reasons that Bennett recorded in her notes, and apparently in his own words, from their February meeting:

| [I find the accordion to be] a fascinating instrument because of the inherent polytonal effects which can be done by the juxtaposition of harmonies presented in the right hand to conflict with the harmonies presented in the bass chord section. This also applies to passing dissonances which here acquire a very pleasing affect because of the ability of the accordion to sustain a pedal bass and pedal point. |

George Kleinsinger in his "jungle" apartment in Hotel Chelsea, January 17, 1962. Photos by Elsie Bennett. Elsie Bennett photo album. |

As with so many composers, Kleinsinger's concept of the accordion was based largely on his near exclusive exposure to its sociological stereotypes, though he spoke of them to Bennett with admiration rather than condescension, as do some composers and non-accordionist musicians:

| The accordion has a wonderful ability to evoke a sort of lyric nostalgia of city life. That's why I've used it in films dealing with city life in Paris and New York. The sound is so strange and different that fortunately it cannot help evoking this nostalgia. |

That having been said, however, the resulting composition used the instrument for its special timbres and idiomatic effects rather than evoking ethnic or popular styles.

Kleinsinger took on the commission with much enthusiasm, stating that he thought the idea of commissioning serious works for the accordion was wonderful and that he looked forward to learning more about its "mechanics" and "complexities" in composing it than his use of it in his film scores had required of him in the past. The result was a delightful, expressive, and harmonically rich little gem that was easy enough for any professional or even moderately advanced student to learn to play within the approximate time the composer took to write it: a month or less.

George Kleinsinger and Elsie Bennett. Kleinsinger's apartment at the Chelsea Hotel. February 4, 1962. Elsie Bennett photo album. |

The baroque-like title, Prelude and Sarabande, is direct enough in describing the larger bipartite form of the work: a somber, plodding opening section (the prelude) of fourteen bars in common meter (4/4 time), marked "lento," that leads attacca into the second major, and much longer, portion of the piece, the Sarabande proper. The Sarabande follows the baroque era formula of a slow, stately court dance in triple meter, often putting emphasis on the second beat of each measure. This does happen often in the left-hand accompaniment to the predominantly right-hand (treble) melody in Kleinsinger's rendering.

Two-section pieces with such generic titles as Kleinsinger's choices were very common in the lute literature of the transitional period from the Renaissance into the Baroque era (nearing the beginning of the seventeenth century). The Sarabande also became one of the common dance forms employed in what was normally a four-movement suite for harpsichord or orchestra in which all the movements were caste in common court dance styles. The order of the formula was usually Allemande (a complex, rather fast, German dance), Sarabande, Courante (a lively French dance alternating between sextuple and triple meter at times), and the lively Gigue (an Irish jig, usually in compound duple meter). Oftentimes, additional "optional" dance style movements, such as the Minuet, the Passepied, or the Gavotte, were inserted as well. The Bach English and French Suites for harpsichord would serve as good examples of this practice.

Such titles, and modern versions of their musical traits as described above, are quite common in the instrumental works of more conservative, "neoclassical" twentieth century composers like Kleinsinger (though perhaps his highly expressive style leans more towards "post-romantic"). This may be easily observed even in the list of commissions for the AAA. Examples include Creston's Prelude and Dance, Brickman's Prelude and Caprice, Diamond's Introduction and Dance, and Flagello's Introduction and Scherzo, to name a few.

Kleinsinger's Prelude opens with a two-measure left-hand motif of five harmonies, three plain triads (C major, A minor, and G major), a C major 9th chord with the 9th, D, in the lowest position, and a polychord combining B-flat augmented and B minor (the result of combining a counterbass B flat with a B-minor chordal button, thus yielding the pitches B flat and D (enough to sound like a major triad), and B natural, D again, and F sharp, forming a complete B-minor triad). Since the progression stops on a G-major triad, the first aural impression might be that it is the tonal center of the key and perhaps in the mixolydian mode (based on a G-major scale with the F-sharp lowered to F-natural); but the G major harmony ends up serving more as the dominant function of the key of C major, the actual tonal center and foundation, indirect though it may be at times, of the Prelude throughout.

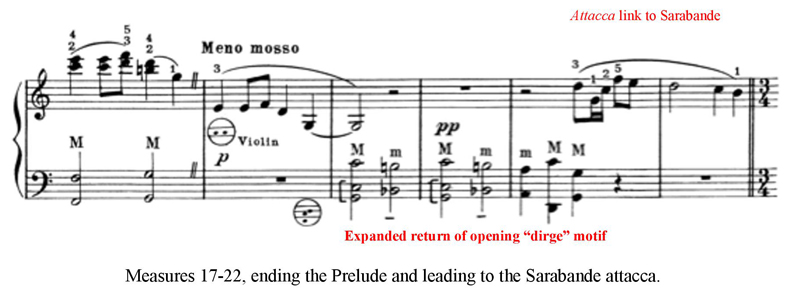

This dirge-like motive returns several times with some variance in the Prelude, with the original chord sequence once again exposed alone and extended slightly at the end. Though this remains an important and noticeable element in the bass throughout the movement, the main melodic theme appears in the right-hand treble part beginning in the third measure.

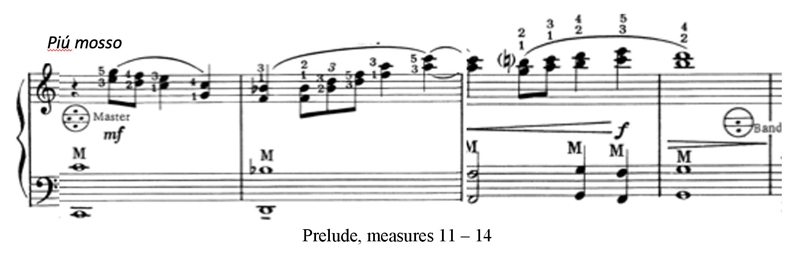

It is initially pensive but flowers forth in a more passionate and cheery mood near the middle of the Prelude where it is marked piú mosso and the tonality seems to briefly flirt with the C mixolydian mode (based on a C-major scale with its seventh note, B, lowered to B-flat).

All is quieted soon, however, by the ritualistic return of the dark opening bass motive at the end of the 22-measure Prelude. A two-measure, right-hand link then quietly and smoothly leads directly into the Sarabande.

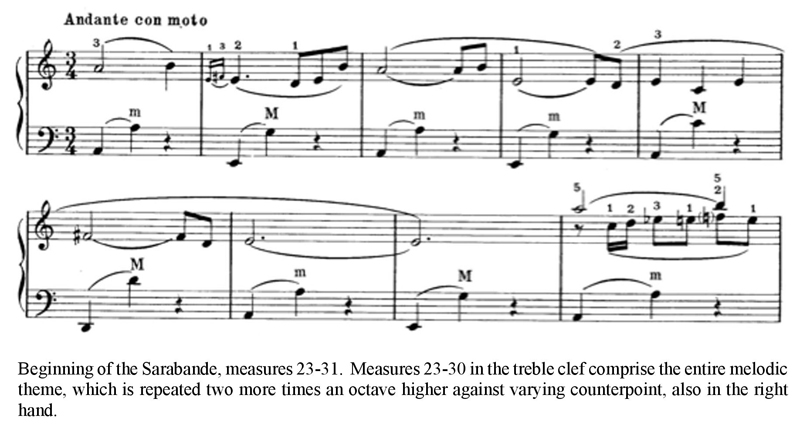

The Sarabande is in a more lilting tempo (marked "Andante con moto") but cannot go forward at too fast a pace lest it lose its dignified status as that dance type. The movement is in a tripartite, A-B-A1 form.

The halting nature of the initial 24-measure A section (measures 23 – 46) is well maintained by the incessant, repetitive left-hand accompanimental figure of two quarter-note "oom-pahs" and a quarter rest which serves as a stabilizing element to the melody unfolding exclusively in the right-hand part. Unlike the Prelude, this part of the Sarabande is essentially in the minor key, suggesting the Aeolian mode (the same as the unaltered pure or natural minor scale) built on A. The right hand is kept busy supplying the song-like, rather melancholy theme accompanied by an active counterpoint which pushes the music forward. The 8-bar melody is immediately repeated two times an octave higher with increasing intensity and yet more busy right-hand counterpoint. This tension between these two elements on one manual supported by the stable bass patterns in the other creates a very lovely and graceful effect.

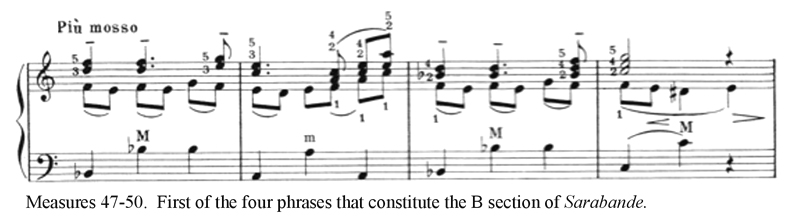

A new melodic theme ensues at measure 47 that falls into four distinct, but somewhat unbalanced, phrases (4/3/4/4 measures each, clearly ending at measure 61). Though in

a rhythmically logical enough design, the melodic lines of each phrase contrast with each other in pitch to such an extent that they might possibly be diagrammed as A/B/C/D rather than the more common 4-bar, "double period" plan with returning phrases within, such as A/B/A/C or A/B/C/B (either design often referred to as "rounded binary form") so common in most conventional tonal music.

As in other parts of the work, the sense of key is ambiguous. The ear might first assume the key of B-flat major due to that triad's strong presence in the first measure (measure 47), which in turn alternates with an A-minor triad in the next measure, suggesting a false leading-tone chord that is a minor triad rather than the normally expected diminished quality; but the phrase ends on a pensive C-major triad, just as strongly suggesting the dominant function in the key of F. The fourth and final phrase (measures 58-61), however, is clearly anchored to the key of D minor, though the replacement of the expected B-flat of that key with B-natural for the 6th scale degree and the lack of the expected C-sharp leading tone in the implied dominant chord of the phrase's third measure once again brings our ears back to modality instead of tonality (in this case, D Dorian mode instead of the conventional D-minor scale source).

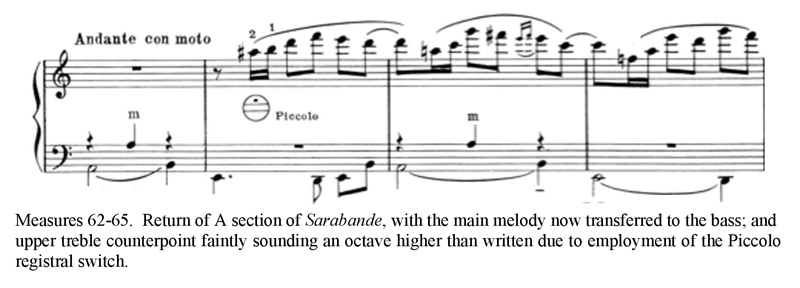

The returning A section material (measures 66-75) is in three distinct segments marked respectively by declining tempi: Andante con moto, Moderato, and Lento. This slowing down of pulse brings the work to a gentle, wistful ending. This time the theme appears entirely in the bass during the first two tempo sections, while still requiring the right hand to supply active, though now more hauntingly sentimental (and, due to the employment of the Piccolo shift, very highly pitched), counterpoint, before it reclaims its original treble position for its fading, resigned, coda-like farewell in the remaining few measures.

A little over a year after its completion the Prelude and Sarabande was premiered by Carmen Carrozza on April 28, 1963, at the second of his historic Town Hall recitals in New York. As has been mentioned in previous articles in this series, Carrozza premiered two other AAA commissioned works on the program, Improvisation, Ballade and Dance, by Elie Siegmeister, and Salute to Juan, by Paul Pisk. Regrettably, there were no New York newspaper critics present at this event even though it was announced that Sunday in the New York Timesi> and briefly reviewed in the June issue of Musical America.

Another noteworthy performance took place a year later, on February 21, 1964, at yet another frequently mentioned concert in this series, that of the Donnell Library, the auditorium of which was a popular venue for many types of events in New York from the time of its construction in the late 1950s through to its demolition in 2008. This time the artist was Robert Conti. More recently, the writer had the pleasure of performing the Prelude and Saraband in the 2004 AAA Master Class and Concert Series, at the Tenri Institute, in New York and as the guest artist in the 2014 annual and always spectacular Christmas Lessons and Carols program by the Westminster Choir College in the Princeton University chapel. It was very warmly received by both audiences, as it more than likely has been at all its other performances by others. Its quiet, meditative, and at times hauntingly melancholy qualities do render it quite appropriate for performance in religious services or other meditative or quiet venues, not to mention fulfilling a role as one of the short and/or slow selections on any recital program.

*Dorothy Richter, "New York's Hotel Chelsea Has Sheltered Many Unusual Persons," The Post-Crescent (Appleton, WI), August 5, 1967, A14. See also Sherill Tippins, Inside the Dream Palace: The Life and Times of New York's Legendary Chelsea Hotel (Boston, New York: Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014).

Hear a performance of Prelude and Sarabande under its listing on the AAA Commissions homepage at www.ameraccord.com/aaacommissions.php

During 2006, Dr. McMahan performed two AAA commissioned pieces, Invention, by Alexander Tcherepnin, and Scaramouche, by John Franceschina, and premiered a new work of his own, Blue Rows, for French horn and accordion, with hornist Linda Dempf, in the evening concerts of the 2006 AAA Master Class and Concert Series at the Tenri Institute, in New York City, July 28-30.

The AAA Composers' Commissioning Committee welcomes donations from all those who love the classical accordion and wish to see its modern original concert repertoire continue to grow. The American Accordionists' Association is a 501(c)(3) corporation. All contributions are tax deductible to the extent of the law. They can easily be made by visiting the AAA Store at https://www.ameraccord.com/cart.aspx which allows you to both make your donation and receive your tax deductible receipt on the spot.

For additional information, please contact Dr. McMahan at grillmyr@gmail.com

2025 AAA 87th Anniversary Festival Daily ReportsJuly 10-13, 2025 Latest News2025 AAA Elsie M. Bennett Composition Competition 2025-2027 AAA Executive Board take office 1st January. AAA History ArticlesHistorical Articles about the AAA by AAA Historian Joan Grauman Morse Music CommissionsHistorical and analytical articles by Robert Young McMahan. Recent articles:

AAA NewslettersLatest newsletters are now online. |