Music Commissions Home | Music Commissions Brief History | Music Commissions Articles List | Composer's Guide to the Piano Accordion

As reported in a previous installation of this series, Elsie Bennett successfully commissioned three new works in 1964, Normand Lockwood's Sonata Fantasy, Nicholas Flagello's Introduction and Scherzo, and Paul Creston's Fantasy, for accordion and orchestra or, as specified by the composer, solo accordion. Having already examined the first two of these compositions in past issues of the Journal, we will now turn our attention to the third of four commissions Creston fulfilled for the AAA over a span of eleven years (the others being Prelude and Dance, 1957; Concerto for Accordion and Orchestra, 1958; and Embryo Suite, 1968, the last to be examined in a future article).

Surprisingly little correspondence between Bennett and Creston regarding the Fantasy appears in the vast quantity of letters and postcards they exchanged over the years and are preserved in Bennett's extensive and well-ordered archive of AAA commissioned materials; and scant mention of performances, both in solo form or with orchestra (including the 1967 world premiere with orchestra), is to be found in the various accordion and musical publications of the time. Bennett's contract files, however, reveal that the invitation and contract to write this second composition for accordion and orchestra is dated July 17, 1964.

Creston must have acted very quickly to fulfill his part of the agreement, since the date appearing under the last measure of the submitted final manuscript to Bennett reads "September 1964," less than three full months after its assignment. Following this is a letter written ten months later, dated July 11, 1965, by Bennett to Creston offering him an honorarium of $100 to be the commentator on his previous two AAA commissions (Prelude and Dance and the Concerto), plus his new offering, now titled Fantasy, at a seminar-workshop for students and professionals planned for May 22, 1966, at the Statler Hilton Hotel in New York City. In the meantime, the score for accordion and piano reduction of the orchestral portion was published sometime during that year by Mills Music and thus made available to the accordion world as a solo or duet.

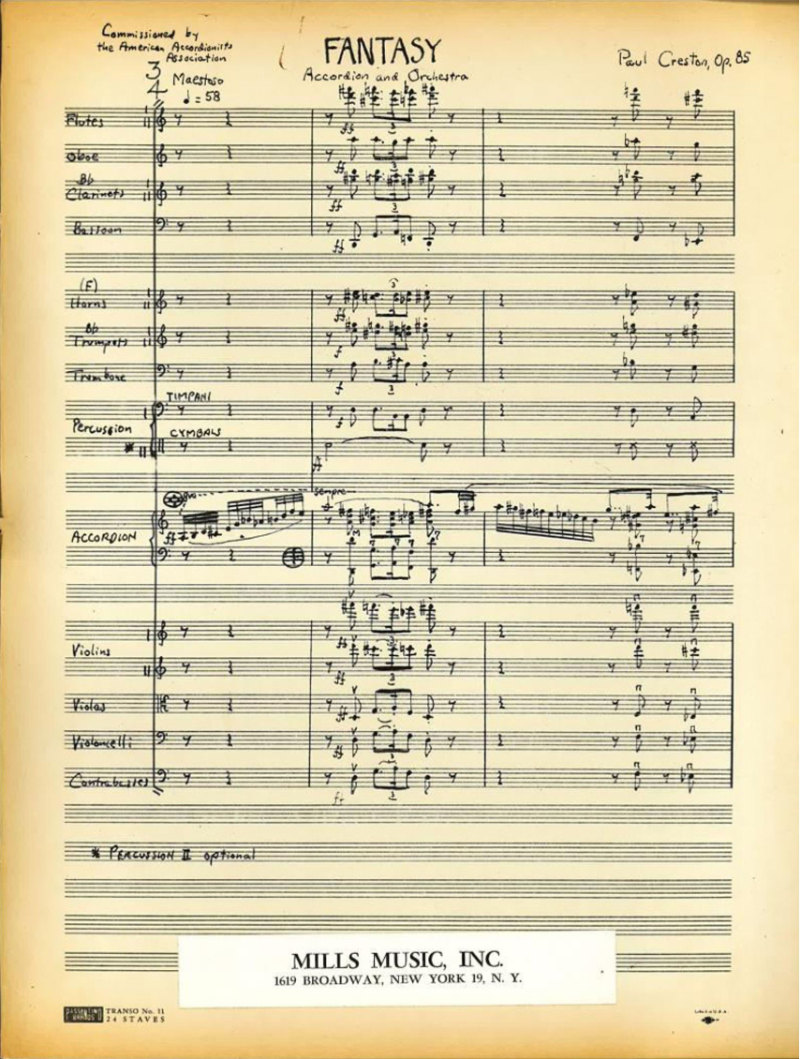

Example 1. First page of Creston's submitted orchestral manuscript of Fantasy to the AAA. |

In a second letter several months later (October 5, 1965), Bennett informed the composer that the renowned artist Daniel Desiderio would play excerpts of the Prelude and Dance and the Concerto plus the entire Fantasy for the occasion. This, then, would serve as the official premiere of the new work in its solo rendering. To accomplish this, Bennett wrote to the publisher, Mills Music, on October 22 to ask for a temporary copy of the score prior to its publication and release, which took place in 1966, and permission for Desiderio to perform it. She also sought to have the Confederation of International Accordionists (CIA) accept Fantasy as the test piece for the Coupe Mondiale international competition in 1966 but wrote to the publisher in November that it was refused. It has yet to gain that distinction.

Example 2. First page of the Mills Music 1966 publication of the accordion/orchestral piano reduction of Fantasy. |

Bennett proudly announced the upcoming seminar/workshop in at least two prominent accordion periodicals, the March 1966 edition of Accordion and Guitar World (vol. 30, no. 5; "Fourth AAA Workshop Features Creston") and the spring 1966 edition of Accordion Horizons (vol. 2, no. 3; "AAA Accordion Workshop Features Paul Creston and Daniel Desiderio"). Though Desiderio was heralded as the performer-to-be in both articles, I was perplexed to see in a third entry in the summer edition of Accordion Horizons (vol. 2, no. 4; "Creston Accordion Workshop Terrific Success"), that, in reporting on the then already past May event, William Schimmel, rather than Desiderio, had been the guest performer. In addition, a photograph at the hotel of Creston, Bennett, and Schimmel accompanied the writing.

Paul Creston, William Schimmel, and Elsie Bennett at the fourth AAA seminar/workshop presentation of commissioned works and premier of the solo version of Creston's Fantasy, at the Statler-Hilton Hotel, New York, May 22, 1966. Elsie Bennett photo album. |

In a recent conversation with Dr. Schimmel regarding this switch in performers, he explained that about a week before the engagement, Desiderio was unable to attend due to some unexpected matter that arose. In what must have been a panicked moment for her, Bennett contacted Schimmel's teacher, Dr. Jacob Neupauer, asking if his then very accomplished eighteen-year-old student would be willing to learn and play the Fantasy, in addition to performing the Prelude and Dance (already in Schimmel's repertoire and that of most of the rest of us competing in the AAA competitions of that time) for the seminar/workshop. He was also asked to play segments of the Concerto to illustrate various points made by the composer in his presentation. Anyone, including myself, who has performed the Fantasy can attest that learning it in a single week would be a Herculean task, for it is every bit as difficult and challenging as the highly virtuosic Concerto, though mercifully shorter in length. Nevertheless, Schimmel carried it and the other assigned works off very successfully, thus gaining the mantle of being the youngest accordionist up to that time to premiere a major AAA commissioned solo.

In recounting this heady experience to me, Schimmel fondly recalled that Mr. and Mrs. Creston and Mr. and Mrs. Bennett took him out for dinner at Bruno's Pen and Pencil Steak House afterwards and that he "felt like a million dollars." He also added that he had already been studying composition with Creston at his home in Hartsdale, New York, and moved to New York City soon thereafter to begin his degree work in Composition at Juilliard. Creston was very pleased with his performances at the Statler Hilton and complimented him publicly. Curiously, Schimmel performed all these works not on his own accordion, but that of Creston (a Sano with the composer's name on it), who, as a pianist and acclaimed organist, took up the instrument for a while and became quite proficient in playing it. This explains, at least in part, why Creston's AAA commissioned works are so well suited to the virtuosic demands and expressive qualities of the accordion and utilize its idiomatic features so well.

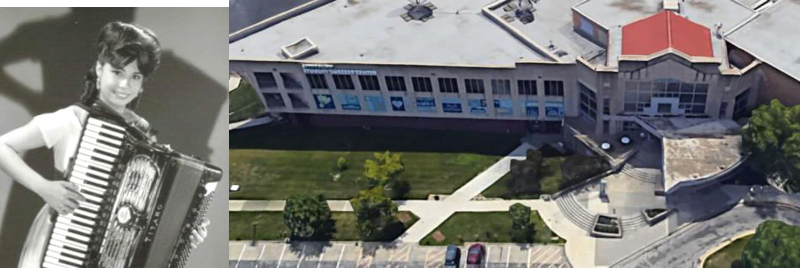

It would be another year before the official premiere of the Fantasy with orchestra would take place. That was accomplished in Pierson Hall at the University of Missouri in Kansas City on Friday evening, March 24, 1967, by another young student of approximately the same age as Schimmel, Betty Jo Stumblefield (now Simon). Stumblefield was a sophomore and accordion major in the burgeoning accordion program established by the noted classical accordionist and trailblazing proponent of new contemporary classical music for accordion Joan Cochran in the Conservatory of Music at UMKC. The concert, entitled "Concerto-Aria Concert," was an annual event in the Conservatory in which top students were selected by faculty from different instrumental and vocal areas. The Fantasy was performed by Stumblefield and the University Orchestra (consisting of UMKC students as well) immediately after the intermission. Regarding this young artist, she, like many others of us who are still active "senior citizen" American accordionists, had already garnered numerous awards (nineteen, according to one local newspaper) in the advanced levels of regional and national competitions, and had made the first playoff of the AAA National Championship Competition the previous year. A few months after the Creston premiere performance she played in a four-month USO tour in Iceland, Greenland, Newfoundland, and Labrador. She remains highly active as an accordionist to this day, playing in regional, national, and international venues, as may be observed in her website, www.bettyjosimon.com, and various Google references.

Betty Jo Stubblefield (now Simon) at the time of her premier of Fantasy with the University of Missouri Kansas City Orchestra at UMKC's Pierson Hall (right), March 21, 1967 |

It is odd that there was no mention of this significant accordion event in any of the known accordion publications and other music trade journals, such as Musical America and Music Journal, to which Elsie Bennett often submitted articles about the latest commissioned works and their performances. Equally unfortunate was the absence of a music critic at the concert, and hence a consequent review, despite announcements of the Fantasy's debut and mention of the accordionist prior to the occasion in two local newspapers, The Suburban and The Kansas City Star.

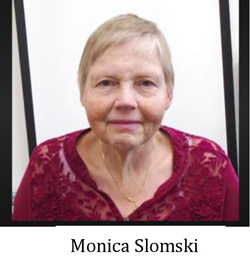

Presently, the writer is aware of only two other performances of Fantasy with orchestra since that at UMKC. Both are listed in the PhD  dissertation of 1975 AAA and 1979 Accordion Teachers' Guild National Championship winner Monica Slomski, Paul Creston: A Bio-bibliography, which was published by Greenwood Press in 1994. They are accordionists Patricia Costagliola, with the Municipal Arts Orchestra, Julius Grossman, conductor, Brooklyn, New York, August 14, 1974; and Slomski, herself, with the Bridgeport Civic Orchestra, Harry Valante, conductor, Bridgeport, Connecticut, March 1975 (exact date not given).

dissertation of 1975 AAA and 1979 Accordion Teachers' Guild National Championship winner Monica Slomski, Paul Creston: A Bio-bibliography, which was published by Greenwood Press in 1994. They are accordionists Patricia Costagliola, with the Municipal Arts Orchestra, Julius Grossman, conductor, Brooklyn, New York, August 14, 1974; and Slomski, herself, with the Bridgeport Civic Orchestra, Harry Valante, conductor, Bridgeport, Connecticut, March 1975 (exact date not given).

The music of Paul Creston enjoyed its greatest popularity and frequency of performance in the 1940s and early 1950s, a period during which he was arguably the most in-demand American composer in Europe. By the 1960s, however, "neoclassical" music of his sort was supplanted in importance by the more abstract, expressionistic offerings of the atonal school, represented by such innovative composers of that era as Milton Babbitt, Ernst Krenek (an AAA commissionee), Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luciano Berio (who did write one work for solo accordion), Pierre Boulez, George Crumb, and many other younger mid-century figures.

Now middle aged, Creston was deemed out of date by his younger peers for his somewhat jazzy syncopated rhythms, extended tertian harmonic structures, bordering on Debussian impressionism at times, and prominent melodic lines, often built on modal and whole-tone scales rather than the full complement of twelve tones. Such traits were by mid-century considered to be overly farmed innovations of an earlier time and past generation. However, such condescension by the musical pendants of the time neither discouraged Creston nor interrupted his steady flow of new works caste in his highly personalized and clearly fixed musical language, archaic though it may have seemed to many. For example, in or around 1964, when he composed the Fantasy, he found the time to also produce four piano solos, three songs with piano, one song for soprano and tenor with eleven instruments, and an orchestral score, The Invasion of Sicily, for the last installment of a seven-episode television series, The Twentieth Century (1958-64).

In addition to composing, Creston also began writing a monumental set of ten books on rhythmic studies for piano, Rhythmicon (1964-77), and completed a second book, Principles of Rhythm, a subject in which he was a recognized and respected authority. In addition to all this creative and academic activity, he remained in his long-time position as organist at St. Malachy's Church in New York, served as the director of the American Society of Composers and Publishers (ASCAP), and was in high demand as both a guest composer and teacher in various venues (including the AAA Seminar/Workshop discussed above).

The Fantasy is a tightly composed one-movement, multi-sectioned work lasting just seven minutes, if played up to its demanding tempi. The orchestration is common for a medium sized ensemble, consisting of six woodwinds (2 flutes, 1 oboe, 2 B-flat clarinets, 1 bassoon), 5 brass (2 horns, 2 trumpets, 1 trombone), a modest array of percussion (2 timpani, tenor drum, played by percussionist 1; and optional cymbals, suspended cymbal, tambourine, triangle, played by optional percussionist 2), and a full string section. The published copy available for sale by Mills Music is for accordion and piano reduction of the orchestral score (arranged by the composer himself) only. As is customary in the music business, the orchestral conductor's score and separate instrumental parts can only be obtained by rental for an agreed upon amount of time (true also of the Concerto and its publisher, Ricordi).

A brief leafing through the score of Fantasy reveals that the accordion plays continually throughout except for only five bars close to the middle point, and that the left-hand part is more often than not duplicated or at least matched in rhythm in the orchestra. Only in the brief opening Maestoso section does the accordion have several measures of extended solo playing (during the last thirteen of the nineteen measures comprising the entire movement). Otherwise, except for a few intermittent exposed moments here and there, the accordion is in constant company with the orchestra. (This is true of the last movement of the Concerto as well, making it, too, a very acceptable solo.)

For all these reasons, the Fantasy can be played with quite satisfying results in any of three ways: as a solo (with the composer's blessings via his note "May be played solo" printed on the front cover of both the published accordion/piano and rental full orchestral scores); as a duet with the easily attainable published piano reduction of the orchestration; or with full orchestra (the rental score). As might be suspected, the solo version is performed most often, but all renderings work quite well as most accordionists who have performed them, including myself, will attest. (Of course, the orchestral version is greatly preferred if that demon of all musical performances, budget, allows!)

When producing press releases of new AAA works, it was common practice for Elsie Bennett to request brief descriptions of them from their composers regarding such elements as form, key structure (when present), tempi, rhythmic traits, harmony, and the like; but, unfortunately, no such documentation from the composer appears in either the Creston/Bennett correspondence or any publication. Thus, I will offer my own analysis and other observations here for the reader's consideration.

A casual glance at the score and its tempo markings will easily reveal that the Fantasy is divided into two major segments, the first marked Maestoso (quarter note equals 58 in tempo), in 3/4 time, and lasting for only nineteen measures; and the second and far longer and complex portion of the work, marked Allegretto (dotted quarter equals 69 at first), enduring for 198 measures, and beginning in 6/8 time.

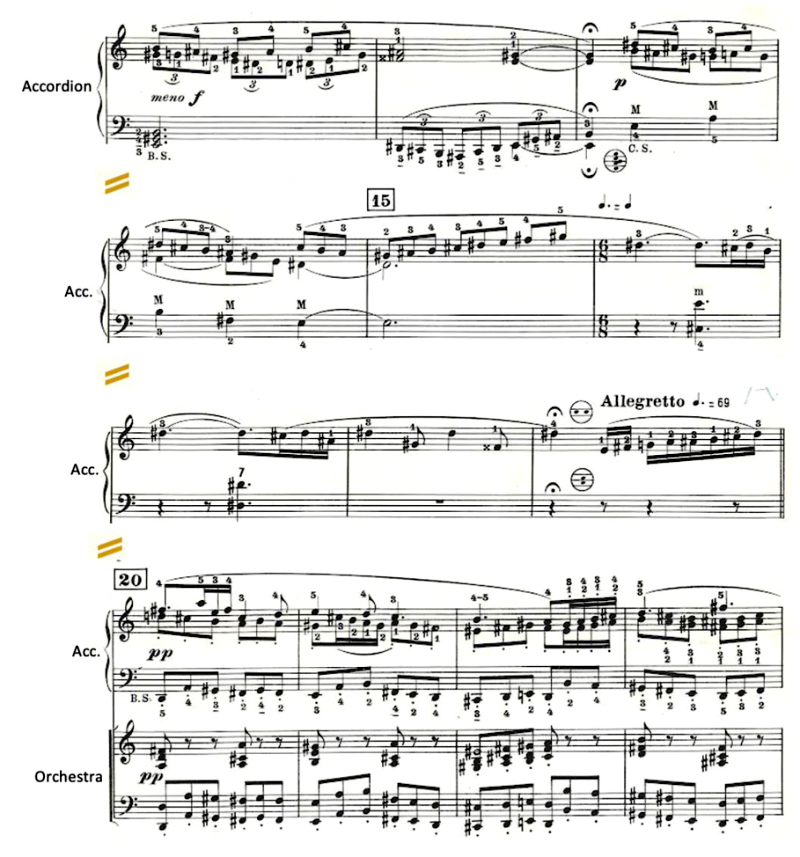

The Maestoso section opens with a bombastic (double forte), declamatory introduction by both the accordion and orchestra that unfolds for ten measures. (See Examples 1 and 2 above). The remaining eight and a half measures of the movement features a quieter, more flowing, but still restless accordion solo that builds in upward moving phrases of eighth notes supported in hemiola by triplets. All eventually lead to a pensive final cadential phrase in a shift to 6/8 time featuring five approaches to accentuated D-sharps before all comes to a calm end on the first two beats of measure 19, prolonged momentarily by a fermata. Then shifting to the lighter right-hand violin and left-hand soft tenor shifts, the accordion remains centerstage by stealthily breaking into a four-beat ascending scalar anacrusis of eight rising sixteenth notes in the right hand that leads to the Allegretto movement proper in the next measure. See Example 3.

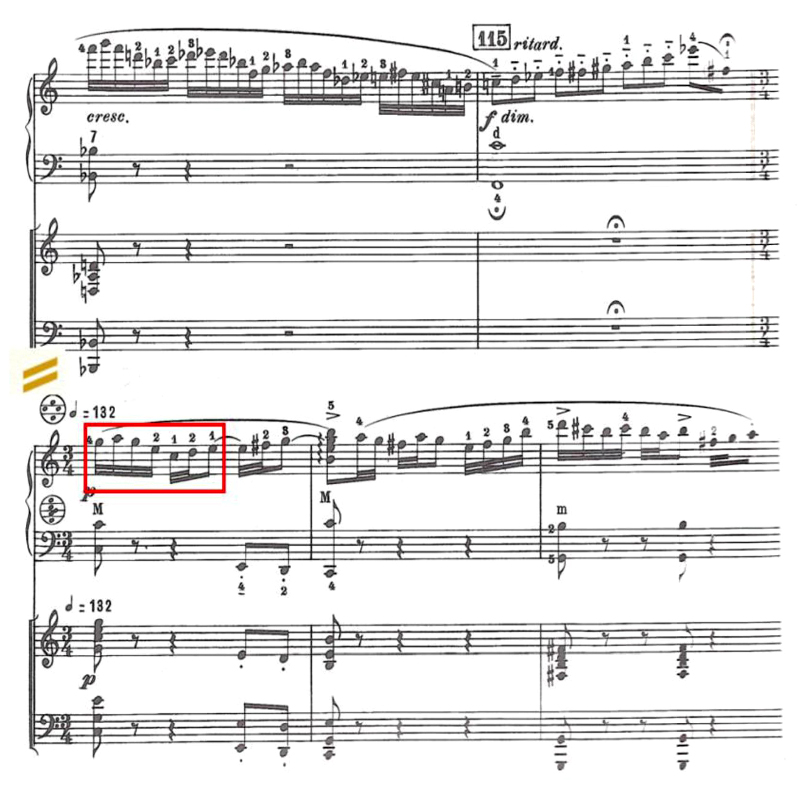

Example 3. Accordion solo at end of the Maestoso leading to the Allegretto section and return of the orchestra |

The far lengthier Allegretto offers many more changes in mood, thematic material, and meter than did the comparatively brief Maestoso. The aforementioned right-hand sixteenth note anacrusis leads into a gently flowing pianissimo melody maintaining the 6/8 meter introduced at the end of the Maestoso, with much two-part counterpoint accompanying it in the middle voice of the same manual while the left hand and orchestra establish a rhythmically steady "walking" bass line of eighth-note values that largely serves to propel the movement's first fifty-nine measures. See the beginning of this new theme in measures 19-23 of Example 3 above.

This ultimately leads to transitional material where, at the end, and for only a brief period of five measures, the accordion has its one and only break from playing in the entire piece, unless, as indicated in the score, the passage is being performed as a solo only and thus must play the supplied optional accordion cue.

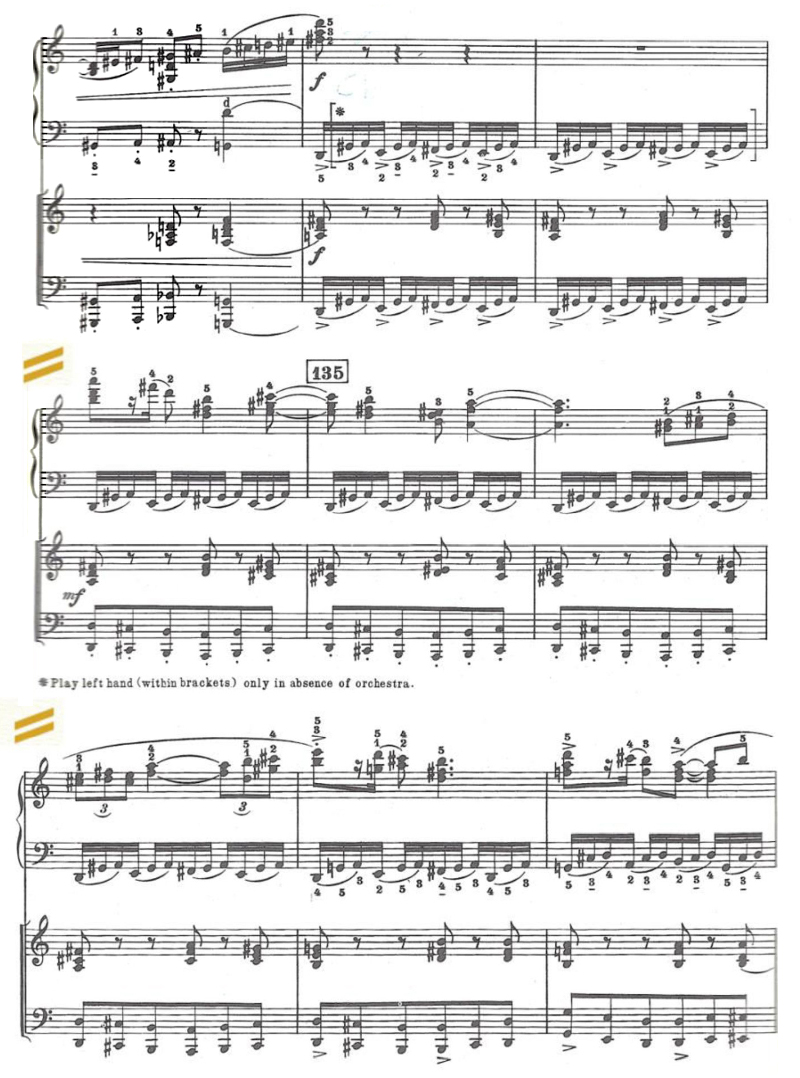

In any event, whether carried by solo accordion or orchestra, the music gently moves into a second theme, in a soft dynamic yet again, but now in 4/4 time and at the slower metronomic marking of quarter note equals 72. The new melody, played by the accordion and accompanied by the orchestra, consists largely of eighth-note triplets vying with sets of two or four eighth notes. The accordion's right-hand melodic line will sound an octave lower than written since it will be employing the instrument's rich, dark "bassoon" register. By contrast, this melody is yet again accompanied in addition to the orchestra, by the misty, higher timbre of the left-hand manual's "soft tenor" register playing similar rhythmic motifs exclusively on the chordal buttons of the stradella system—a lovely, transparent effect. See Example 4, beginning with measure 86.

Example 4. End of the brief and only lone orchestral interlude in the Allegretto and beginning of the second theme (measure 86) and slower tempo with the return of the accordion sharing thematic content with the orchestra. |

Intensity once again builds towards the end of this section, and, after a cathartic mini cadenza of two measures by the accordion alone, the passage leads into what might be conceived of as a rondo encapsulated within the larger movement. The meter once again changes, this time to 3/4, and the registers of both manuals of the accordion open all the reed ranks (the "master" shifts) for major bombastic effect. The main melodic motif from which varieties of consequent melodic lines will now flow from each of its eight intermittent and often transposed reappearances in this especially lengthy and more urgently lively (quarter note equals 132) portion of the movement might remind one not too subliminally of the beginning melodic contour of the children's song "London Bridges Falling Down." See Example 5.

Example 5. Rondo-like section whose principle returning motif (encased in red in example) reappears eight distinct times, though often transposed at different levels, over a range of 95 measures, and each time varying in its melodic development. |

Two distinctly contrasting sections to this "A" thematic element are wedged between its many occurrences. The first of these, which will be called here a B theme, is played by the accordion with orchestral accompaniment and features a strongly contrasting and typically "catchy" Crestonian 16th-note accompanimental figure in the left hand driving the also characteristically Crestonian syncopated, mostly chordal treble theme heard above it in the right hand. Undergirding this 23-measure passage is an additional accompanimental pattern, an unrelenting eighth-note bass line beginning with the descending and then ascending upper tetrachord of the major scale for several measures before moving to other levels and variants, but never ceasing until the end of the section. See Example 6 for further elucidation and information.

Example 6. First clearly delineated contrasting theme to the frequently returning "A" motif displayed in Example 5, with, in the accordion part, syncopated left-hand 16th--note accompaniment (due to special phrase markings) supporting a likewise syncopated melody in harmonic 6/3 triads and other chords and dyads, largely in 3ds, in the right hand. Undergirding the accordion are sporadic eighth-note triads in a recurring rhythmic pattern occurring alternately between the brass and woodwinds against steadily repetitive marching and mostly scalar eighth note octaves in the low strings. |

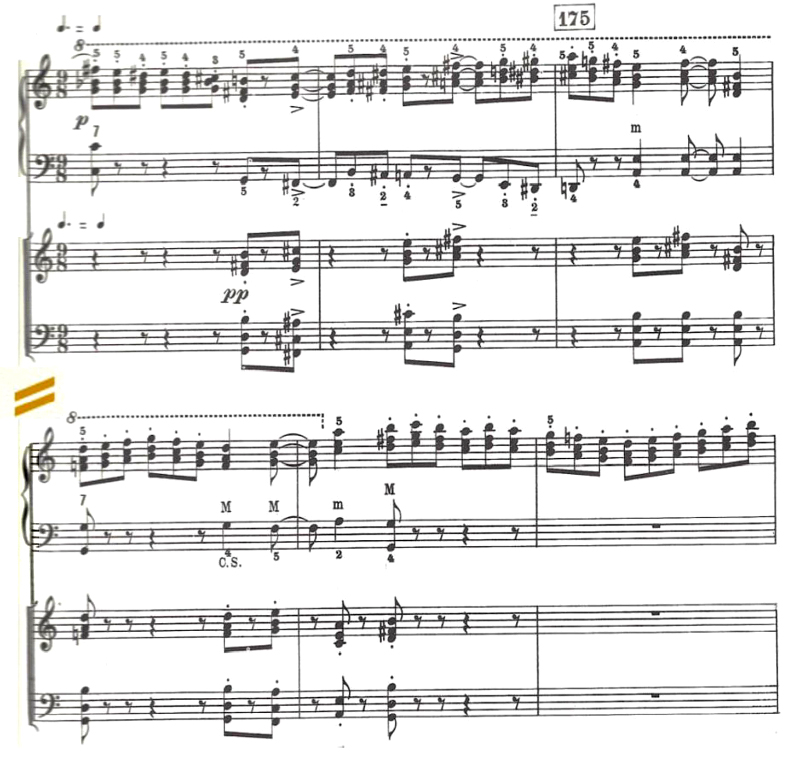

Two bellows-shaking measures of a rising scale of parallel dyads in 3rds climax with the return of the A motif which moves in yet more varied directions than its predecessors, using many flashy scalar passages. After seventeen rambunctious measures, an upward sweep of sixteenth notes collides with the earlier predicted "C" theme. This new section, in 9/8 time (with its predecessor's dotted quarter note value now equaling a quarter), is completely homophonic, consisting exclusively in the right hand of 6/3 triads, most of which are major or minor qualities that sometimes form mild dissonances or extended 3rd harmonies with chordal bass buttons in the left hand. See Example 7.

Example 7. Beginning of the brief and entirely homophonic "C" theme of the embedded rondo-like portion of the Allegretto. |

The briefest section of this embedded rondo within the movement, it leads after only nine measures to what will be the final occurrence of an A motive-developed section. Unfurling yet more fast-fingered technical feats beyond those of previous sections of the movement, the line flies through 28 frenzied measures before the final climb of eight more measures that constitute an upward sweeping coda-like passage that cadences on a final, abruptly climatic A-major triad at the zenith of the accordion's piano key range.

Never once is the accordionist allowed to lose concentration throughout this "rondo" or, for that matter, the entire Allegretto section. Hazardous technical challenges lurk around every corner at often reckless speeds, given the rhythmically intricate counterpoint and small note values that prevail. Nevertheless, the composer was very familiar with the piano/stradella accordion and knew just how far he could push the virtuoso accordionist. This he did magnificently in the Fantasy as he did in the other three masterly works he contributed to the classical accordion repertoire through the AAA. It is neither rash nor an exaggeration to insist that all four -- the solos Embryo Suite and Prelude and Dance and the orchestrally accompanied Concerto and Fantasy -- are mandatory repertoire for the classical concert accordionist. The same may very well be claimed by saxophonists and percussionists (specifically, marimbists) for Creston's equally major contributions to their concerto repertoire.

I am indebted to Dr. William Schimmel, Betty Jo Simon, and Dr. Monica Slomski for their valuable contributions to my gathering of information for this installment.

In 2012, when the original version of this article was published, Dr. McMahan performed one of the recent AAA commissioned works of that time, Canto XVIII, by Samuel Adler, in addition to his own Romp III, for accordion and piano (with Dr. Joanna Chao, pianist), and Sonata Valtaro, for accordion and piano, by William Schimmel (with Dr. Schimmel, piano), all at the eighteenth annual AAA Master Class and Concert Series, Tenri Institute, New York City, during the weekend of July 27-29.

The AAA Composers' Commissioning Committee welcomes donations from all those who love the classical accordion and wish to see its modern original concert repertoire continue to grow. The American Accordionists' Association is a 501(c)(3) corporation. All contributions are tax deductible to the extent of the law. They can easily be made by visiting the AAA Store at https://www.ameraccord.com/cart.aspx which allows you to both make your donation and receive your tax deductible receipt on the spot.

For additional information, please contact Dr. McMahan at grillmyr@gmail.com

2026 AAA 88th Anniversary Festival Daily ReportsAugust 13-16, 2026 Latest NewsAn Accordion Extravaganza! exciting concert, April 26th, NY. 2026 AAA Elsie M. Bennett Composition Competition 2025 AAA Elsie M. Bennett Composition Competition Results AAA History ArticlesHistorical Articles about the AAA by AAA Historian Joan Grauman Morse Music CommissionsHistorical and analytical articles by Robert Young McMahan. Recent articles:

AAA NewslettersLatest newsletters are now online. |