Music Commissions Home | Music Commissions Brief History | Music Commissions Articles List | Composer's Guide to the Piano Accordion

It is interesting that, unlike the first AAA commission for accordion by Alexander Tcherepnin, Partita, there is no known publicity of or article on his second, Invention, or his third, Tzigane, in the accordion periodicals of the time, nor is there any documentation of an official premiere for either. Both are, however, listed, along with Partita, among the composer’s works in the major musical reference resource Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, thus at least making them known to the music world at large.

Partita was the twelfth AAA commission, and was published in 1962, two years after its contract date. * Similarly, a March 1965 letter from Elsie Bennett authorized the composer to write a second, shorter solo (which he was to eventually entitle “Invention”), but it did not appear in print until late 1968. The delay in publishing as well as publicizing Invention may be due in part to the heavy load of other commissions assigned to this acclaimed and much sought after composer as well as a busy piano concertizing schedule (often involving his playing his own works), and, as Bennett expressed to him in a letter, a period of disabling mourning through which she was going since the death of her husband, Mortimer, in December 1966.

Yet another possible obstacle to getting underway with Invention is a third contract Bennett offered Tcherepnin, dated March 25, 1965, a day after that for Invention. He signed and returned both contracts to Bennett by mail in May of that year. For the larger project he was to compose “a Rhapsody or any other short form for orchestra and solo accordion, not less than 7 minutes in duration,” to be completed and submitted by December 1, 1966, and for which he was then to receive $1,000. This was not to be, however. In his letter of condolence to Bennett a month after her husband’s passing, he explained that he would be too busy that year to begin the “Capriccio,” as he was now calling it, or, for that matter, the “solo piece” (again, what was to be “Invention”), the contract of which carried an even earlier deadline of June 1966 (hence already passed).

Alexander Tcherepnin with wife, pianist Lee Hsien Ming, and Elsie Bennett at a Brooklyn Music Teachers Guild event, May 7, 1965, shortly after being commissioned to compose Invention and Capriccio and two years before the commission for Tzigane. Elsie Bennett photo album. |

The composer’s “tardiness” in fulfilling his AAA contracts was mainly due to a tour of performances he was giving throughout Europe of his fifth piano concerto and an upcoming recording date in Paris of the same with RCA Victor, all of which would fully occupy him up through early September. 1966 also saw the publication of his Harpsichord Suite, Op. 100, Sonata da Chiesa, Op. 101, for solo viola da gamba and chamber orchestra, and Mass, Op. 102, for three female voices. ** In addition, he had recently had his sixth piano concerto, Op. 99, published the previous year. Though these works were certainly composed earlier than late 1965 and 1966, time would likely have had to be given to editing the works for publication and consulting with publishers, thus putting yet more pressure on the composer in 1966.

As a result of all these earlier commitments, Tcherepnin therefore understandably expressed doubt to Bennett that he could turn out works of quality during the scant three months the fall would permit. Bennett consequently waived the deadlines for both assignments, but the larger of the two apparently never got off the ground despite this extension. The other did succeed, however, though at least two and a half years past the original contractual deadline of June 1966, as mentioned above. During these years (1965-68) Bennett found time to commission five other composers and both publish and publicize their new works: Prelude of the Sea, by Carlos Surinach; Introduction and Dance, by David Diamond; Danza Ritual and Passacaglia and Perpetuum Mobile, for Accordion, Strings, Brass, and Percussion, by Jose Serebrier; and Lilt, by William Grant Still. (All but Serebrier were “repeaters” who had been previously commissioned by the AAA; these later contributions will be discussed in future articles in this series.)

There are no records or correspondence in the Bennett archive that reveal the compositional process or goals of Invention. Only two documents exist regarding the piece. The first is the aforementioned letter of “authorization” (rather than the usual AAA official contract form), dated March 24, 1965, by Bennett, to Tcherepnin to compose an “unaccompanied accordion solo of not less than 3 minutes in length of any nature of your choosing,” and for which he is to be paid $125, $50 of which is to serve as an advance on royalties to be paid by the publisher (stipulated to be O. Pagani). The second appears over a gulf of three and a half years. Dated November 19, 1968, it is again from Bennett to Tcherepnin informing him that Carmen Carrozza has supplied fingering for the left hand part of Invention (the first time the title is mentioned in the correspondence) and that the manuscript is in the hands of the printers for publication by O. Pagani, which will hopefully take place by early December.

It may be safely assumed that the assistance supplied by the materials regarding composing for the accordion Bennett sent to Tcherepnin when he wrote Partita in the early 1960s as well as Carrozza’s test playing of the first draft and making necessary suggestions and changes with the composer at that time buoyed Tcherepnin when he wrote the final two commissions later. Nevertheless, he did ask Bennett in his correspondence with her about the ill-fated Capriccio to coach him in writing for accordion with orchestra when he could find the time to commence with that project; and, in another letter, Bennett offered to assist him in writing at the elementary level (about which more below).

The production of Tzigane generated considerably more correspondence than did Invention. The earliest hint of this piece being commissioned may be found in a note of Bennett’s to herself, dated June 15, 1966, and indicating that she had sent copies to Tcherepnin of the earlier AAA solo by George Kleinsinger, Prelude and Sarabande, and the just-published Prelude of the Sea (the contract for which bears the same date as that for the never realized Capriccio of our subject), by Surinach. They were clearly examples of modern works aimed at the intermediate rather than advanced accordion student. Whatever elements may have been technically challenging to those in the former level were balanced by their relatively short durations.

Bennett was advised by noteworthy accordion teachers of the time that there was a need for such shorter, easier works as the above to be assigned to commissioned composers occasionally to help students broaden their repertoire from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century transcriptions to twentieth-century original works during their intermediary stages of development on their instrument. These two offerings would serve as good models for Tcherepnin to achieve this goal and write easier, shorter pieces than his more difficult and lengthy Partita that preceded them. In fact, except for Serebrier’s Passacaglia and Perpetuum Mobile, all the current pieces of the other composers just mentioned were commissioned with that express purpose in mind and succeeded in carrying it out.

Furthermore, these works fulfilled another purpose in both state and national AAA competitions: test pieces for intermediate level divisions (as did the more difficult, lengthier commissions for the advanced divisions). Also, accordion adjudicators sometimes complained that the longer test pieces (such as Creston’s Prelude and Dance and Flagello’s Introduction and Scherzo) took too much time in the highly enrolled contest categories of those burgeoning years of the accordion and that shorter ones would be welcome. Whether or not Tzigane was intended to fulfill this need is conjectural for a couple of reasons to be explained below.

The contract for Tzigane was issued on July 14, 1967 and was apparently retroactive to the actual composition of the piece, reading as follows: “The [AAA] hereby agrees to pay you [Tcherepnin] the sum of $51 as payment in full for the piece ‘TZIGANE’[sic] which we have just received. ($50.00 of this $51.00 will be an advance on royalties to be paid by Pietro Deiro Publishers.)” Tcherepnin, always business minded, penciled in the addendum “that will be 10% of the selling price.” The contract was in compliance with a proposal by Bennett in a letter accompanying the contract in which the conditions would be that 1) The piece would be published by Deiro; 2) the composer would accept a $50 advance on royalties up front; 3) he would allow the AAA to take credit for commissioning this pre-existing piece and “make it legal” via a one-dollar fee to him to show it was commissioned.

An earlier post sent on July 4 by Tcherepnin to Bennett contained a copy of Tzigane and a note that suggested that Bennett may have requested an intermediate level piece from him, already knew that Tzigane existed, and wished to examine it, perhaps to see if it fit her description of what she wanted:

| According to your suggestion, I am joining herewith the photostat reproduction of the Tzigane, that I have edited according to your indications. I realize that it is not a piece for beginners, rather a concert piece. So even if you feel that it is worthy for publication and find a publisher for it, I expect to do the beginner piece sometime during the fall before starting the composition of the Capriccio. |

From this statement it is clear that Tzigane was offered simply as a piece he wrote that might find a place in the accordion repertoire but not necessarily aimed at either the intermediate or beginning student. In fact, it is quite virtuosic, if short. Actually, Invention, though challenging in places, is quite similar in difficulty and length to the intermediate level works contributed by those mentioned above by other composers, and would certainly join their ranks comfortably. Also, it appears as if Bennett was not seeking another intermediate level “test piece” for competitions at this point after all, but rather something truly for the beginner. Therefore, Tcherepnin’s offer to compose a “beginner piece” seems to be taken up by Bennett in a letter she sent Tcherepnin a half year later on January 4, 1968:

| I was thinking about your solo piece . . . and I want to remind you that the piece should be very easy. I had hoped we could use it in the early teaching grades. It is hard enough to be a composer, and inspiration is important, but it is really difficult to compose something easy but interesting. It is also very difficult to make the piece modern and at the same time easy, and especially hard to write the piece as it doesn’t sound like our old-fashioned music in a tonality and at the same time easy. You have a very hard job on your hands. . . . I really am good at one thing—that is knowing if it is easy or not. I have learned the hard way, through about 30 years of teaching . . .. |

As with the Capriccio, however, there is no evidence that Tcherepnin ever found the time in his busy schedule to write such a piece, and no contract was ever formally offered to him to do so.

Alexander Tcherepnin and Elsie Bennett at her Brooklyn home, February 4, 1968, several months before publication of Tzigane and Invention. Elsie Bennett photo album. |

The titles of all three of Tcherepnin’s accordion solos are generic and denote a time-honored musical format and/or style of music. “Partita” is derived from the baroque era and generally consists of an introduction or prelude followed by a variety of short movements in varying tempi and character usually employing popular dance forms of the Baroque era, such as the sarabande, courante, allemande, gigue, minuet, and others. The six Bach Partitas for harpsichord, composed in the 1720s, constitute famous examples of such a plan. However, while Tcherepnin’s Partita certainly also falls into several movements, it does not follow the dance traditions of Bach’s day.

The term “invention” stems from Italian contrapuntal improvisations in the seventeenth century which led to what were typically short one-movement pieces with special and novel devices, such as imitative counterpoint, extensive development of clever motifs, and a variety of moods. Referring again to Bach as the culminating master of that era, his two-part and three-part Inventions for harpsichord are famous examples, although many composers, including the writer, have applied the title to similarly short, experimental pieces of various sorts ever since in the modern musical languages of our own times. (For example, see the writer’s Three Inventions for clarinet and accordion on YouTube).

“Tzigane” is derived from the Hungarian cigány. It is a general term referring to gypsy or gypsy-like music suggestive of eastern European ethnic styles. This usually translates into lively tempi with much bravura and featuring melodies built on odd scales (i.e., not built on the common major and minor scales of Western European tradition). Ravel’s rhapsodic Tzigane, for violin and piano, is perhaps the most well-known work of this title from the twentieth century.

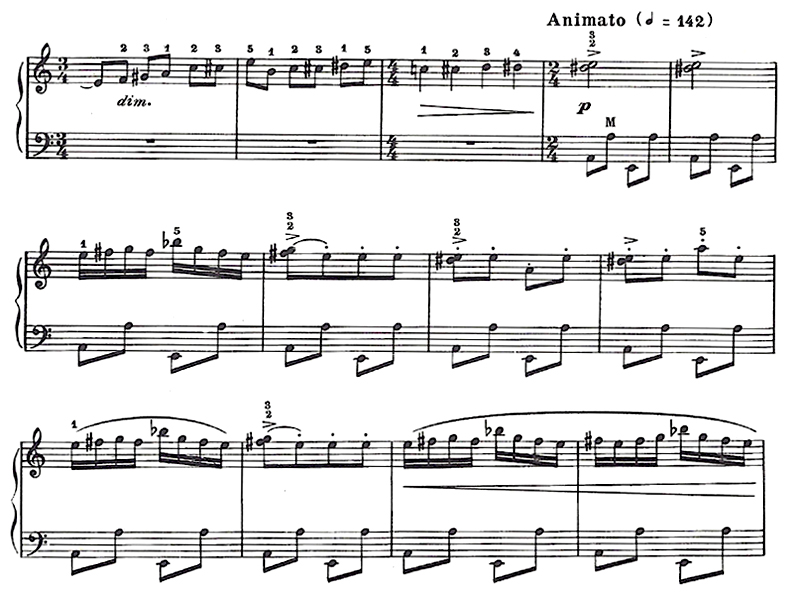

Most of the Bach Inventions resemble the form of the fugue and thus carry a single thematic idea (called the “subject”) from an opening “exposition” of two-part or three-part imitative counterpoint through a series of developmental episodes, modulating in a rhythmically flowing, unbroken manner through various related keys to a climatic ending that often gives one final, dramatic restatement of the subject. By contrast, Tcherepnin’s Invention, though dressed in modern chromatic lines of counterpoint with occasional dissonant clashes between parts at the outset, tends to fall into distinctly contrasting motivic sections that do not resemble the baroque tendency to develop a single motive throughout.

Contrasts of tempi, with many expressive moments of accelerando and ritardando abound, and there are three contrasting motifs that occur in exchange with each other in its various sections. The overall form might be described as vaguely rondo-like, with coda, that divides into the following sections:

| (marked “Slowly” ♩ = 48; measures 1-11). Highly chromatic, non-tonal, though rhythmically regular, style, with clear phrasing and cadence points. Balance throughout between homophonic and contrapuntal textures. |

Beginning of Invention, measures 1-7

Beginning of Invention, measures 1-7

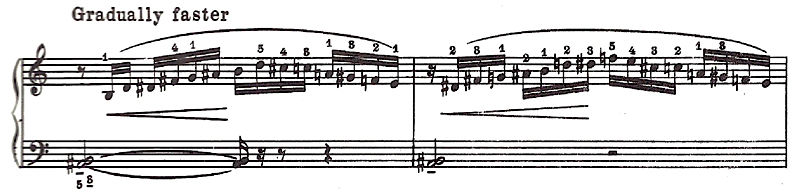

| “Slightly faster” (measures 12-14), a singing melodic line driven by a lower staccato and octave-displaced, chromatic scale-derived accompanimental ostinato in sixteenth notes that is shared between the right- and left-hand parts. This leads to a new, more urgent sixteenth note passage with the tempo marking “Gradually faster,” (measures 15-19), in which appears in the treble clef of the first half of measure 15 the hexatonic “augmented scale,” consisting of overlapping arpeggios of two augmented triads a perfect 5th apart (measure 15), in this case formed by G-augmented and D-augmented overlapping triads (G-B-D# and D-F#-A#), linearly arranged from B upwards in the score, thus forming the clearly visible scale of B D D# F# G A#, and a resultant pattern of alternating minor 3rds and minor 2nds, or their enharmonic equivalents. This is followed in measure 19 by the same arrangement of pitches and rhythm, only starting on the 3rd note (D#) of the scale (i.e., a “rotation” of the scale’s notes), during, again, the first half of the measure. The second halves of these measures also make use of the scale, this time the result of overlapping F- and C-augmented triads and moving in a downward direction. This scale occurs in part or whole elsewhere in the work, though less linearly and thus less conspicuously, and has been employed in many twentieth century works, including jazz. |

| “Return to ♩= 63;” measures 20-22). Similar to section B, at first, but sounding a perfect fifth higher and ending its now truncated “Gradually faster” section (end of measure 22 through measure 24) more dramatically and dissonantly as it climbs to the cathartic, fortissimo climax of measures 25 through 28, marked “Slowing down gradually” and consisting of a homogenous, highly chromatic and dissonant combination of major, minor, and split major/minor triads, major/minor 7th, fully diminished 7th, and augmented/major 7th chords, quartal/secundal chords, and some freely dissonant simultaneities, over a prolonged E pedal point bass note that eventually descends by half steps in contrary motion to the treble’s rising upper part as part of four prolonged, dramatic half note values leading to the next (“C”) thematic section. |

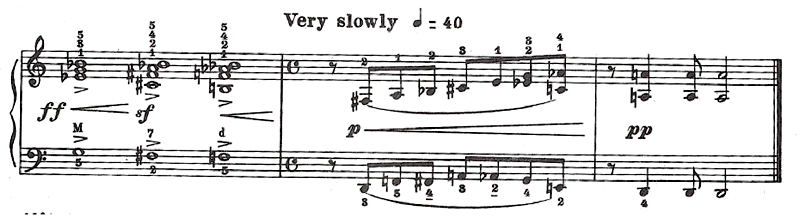

| A return of the A section’s tempo marking (“Slowly, as at the beginning ♩ = 48”, measures 29-38), but not its original thematic material, which is intervalically highly homogenous and often dissonant. The section cadences on a sustained C-diminished 7th chord with an additional dissonating pitch of G# that gives the impression of a dominant function introducing the final section of the piece the composer labels as “Cadenza.” |

| final section, D, marked as a “Cadenza” (♩ = 92; measures 38-45). The cadenza consists of many rapid, gradually expanding upward moving sixteenth-note triplets based on nine-note scales made up of a chain of three beginning minor scale trichords (major 2nd to minor 2nd, forming the outer interval of a minor 3rd), each separated from the other by a half step. |

| The line then shifts direction, picks up speed (marked in groups of eleven and fifteen notes to the beat), and plumets down to three dramatic whole-note polychords, after which the piece ends with two unexpectantly slow and quiet measures (“Very slow ♩ = 40”), the first of which is reminiscent of rising eighth-note figures from section A, and the second of which solemnly sounds the final chord, a hollow sounding D harmony minus its third, three times. |

Despite its near-atonal chromaticism and contrapuntal dissonances, there is a subtle Russian flavor in the music reflecting the composer’s heritage. Another interesting feature of this piece is that it only uses the left-hand chordal buttons once, three measures from the end, where the afore-mentioned three massive, dissonant polychords require multiple pitches in both hands. Therefore, the piece may be played equally well on either the stradella system (for which it was conceived) or either of the two prevalent free bass systems (including the chordal button measure where the left-hand chordal buttons can easily be duplicated by three- or four-finger figurations).

While there is no known commentary by Tcherepnin or Bennett on either Invention or Tzigane in any of the accordion periodicals of the time or the surviving correspondence between composer and commissioner, there does exist an interview between them appearing on the back cover of the published Pietro Deiro Publications score of Tzigane that briefly explains the composer’s inspiration to write a “gypsy” piece and describes the general form and character of the work:

| "30 years to realize this ambition", says the author Alexander Tcherepnin when interviewed by Mrs. Elsie Bennett of the American Accordionists’ Association. |

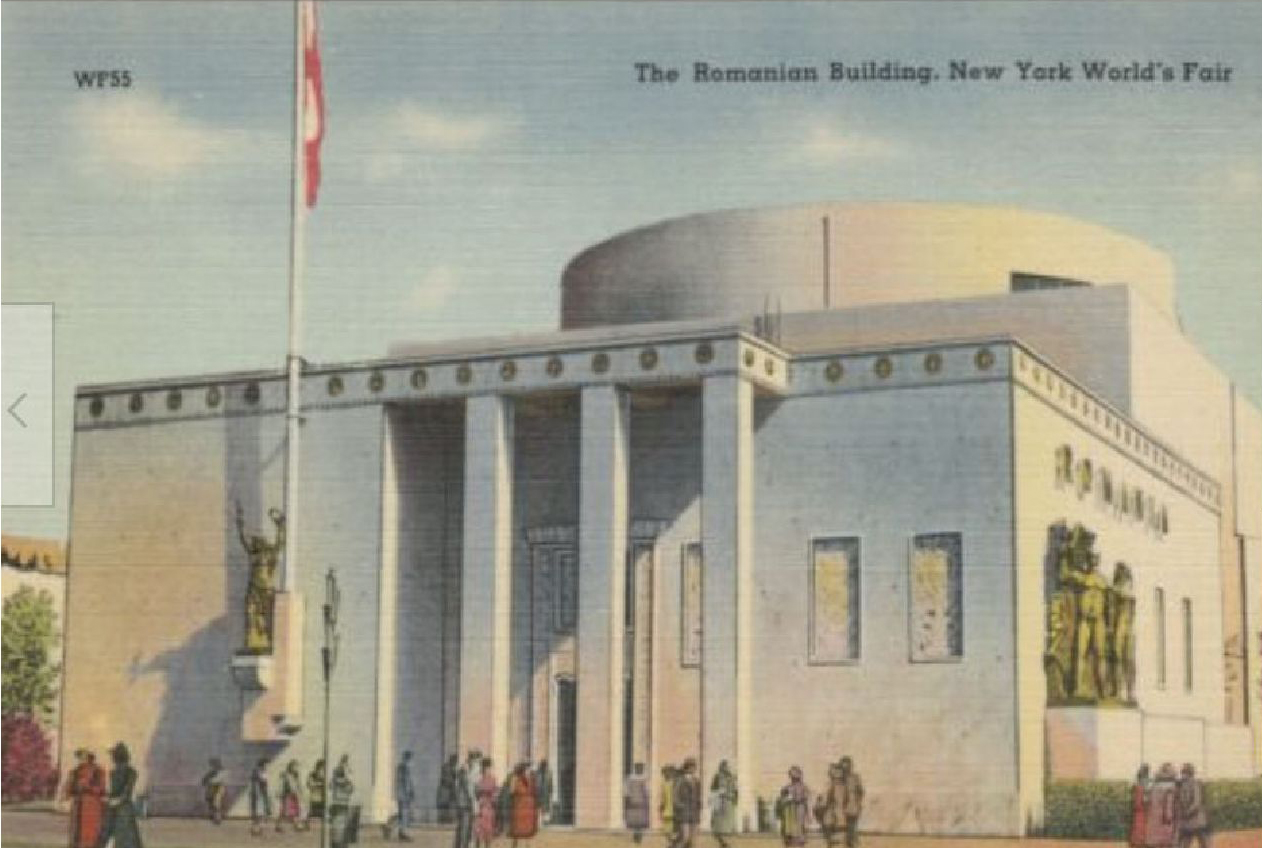

It was at the Roumanian [sic] Pavilion in the [1939] World Exposition in New York City that I [Tcherepnin] was impressed by the music of a performer playing the popular Roumanian recorder. The character of the music remained with me and it was only now with “Tzigane” that I have been able to cultivate the sounds and thoughts of the time. None of the themes used in "Tzigane" are folk themes yet the Roumanian gypsy character persists. Its grandioso type introduction of an improvising nature leads to a fire-like gypsy dance which becomes the climax of the piece. Since my first composition for accordion, I felt a great urge to further explore the possibilities of this instrument. All of this led to this sincere effort “Tzigane,” dedicated to you [Elsie Bennett] for your persistent efforts in acquiring new music for the accordion. |

| [signed] Alexander Tcherepnin |

|

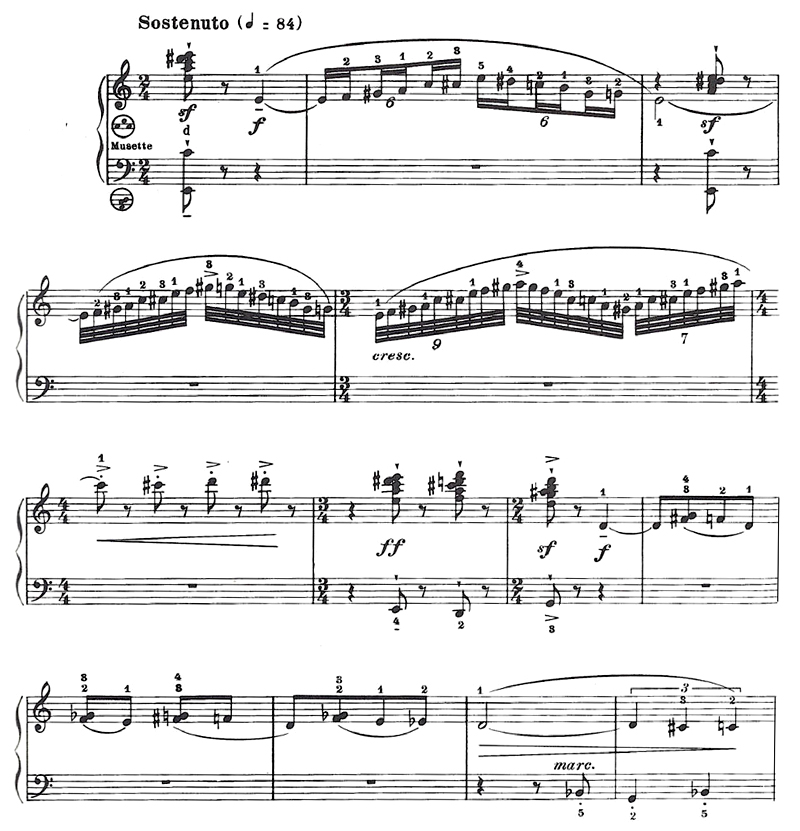

The gypsy flavor of the opening slow section (“Sustenuto ♩= 84”), in which the meter frequently shifts between 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, and 6/4, is largely attained by passionate, bravura melodic lines that frequently break into rapid, flamboyant thirty-second-note runs using the above described “augmented scale” and other eastern European-type scales made up of conventional Western half- and whole-steps mixed often with less common augmented seconds (also prevalent in the music of the Mid-eastern cultures further south).

This exotic effect is occasionally punctuated with strongly accented, dissonant polychords and fortified with long sustained notes in the bass (though all the real action is carried by the right hand in this section).

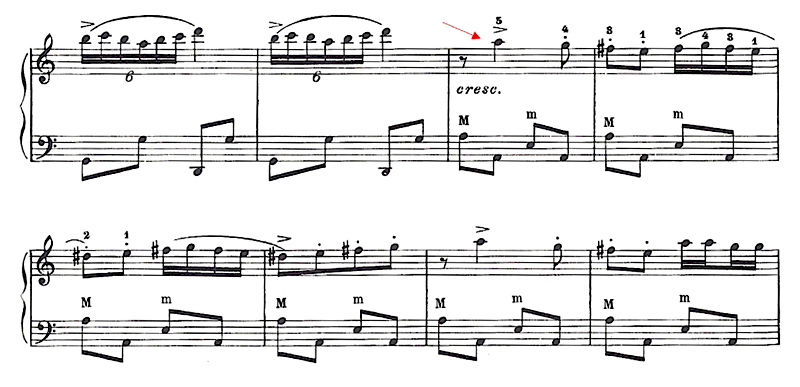

The lengthy, thirty-nine-measure prelude finally climbs upward to the lively “gypsy dance” section (“Animato ♩= 142”), which begins quietly at first but grabs our attention with its employment of frequent, highly dissonant, accented harmonic dyads in minor 2nds. Note also that the melody is in a very limited range and employs only six notes (D# E F# G A Bb) formed by alternating half and whole steps, suggesting a non-Western, faux eastern European-type scale.

A second prominent motif, starting as a downward-falling, scalar figure (first occurrence indicated by arrow in the following excerpt), and, as with the previously described theme, highly chromatic, and caste in a very narrow range, occurs three times at different points in the piece, starting on A twice and then transposed a perfect 5th higher to E near the end of the dance.

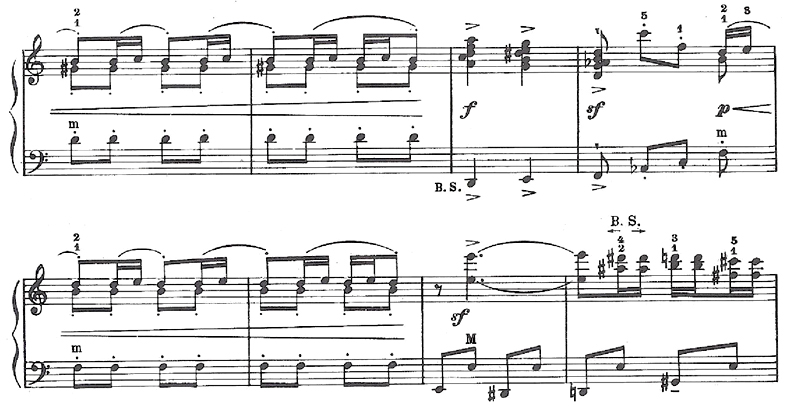

At other moments, the rushing, steady flow of the line is disrupted by sudden rough rhythmic and often more homophonic “bumps,” such as the following:

This fevered eighty-three-measure romp persists to the end in an otherwise steady 2/4 meter, driven by whirling sixteenth notes in the right hand and an incessant oom-pah accompaniment (sometimes reversing to “pah-ooms”) in the left hand.

All ends abruptly with two measures of split-3rd B-major/minor sixteenth-note arpeggios, crashing into four massive, multi-note, highly dissonant staccato simultaneities, the last of which is based on A, the “key” in which the movement began.

Both Invention and Tzigane hold their own quite successfully with the more extensive, varied, well known, and frequently performed Partita and deserve equal status with it. It is hoped that our young and upcoming artists will give this delightful trilogy of contrasting works its proper due in future programs and recordings.

*See the updated, expanded 2003 AAA Festival Journal article in this series regarding both the composer and his creation of Partita for the AAA and for a background to the present article.

**For some reason, Tcherepnin never gave opus numbers to his three accordion pieces as well as a few other works for other instruments. See “Alexander Tcherepnin: A Generic Catalogue of Works,” by Lily Chou, at http://www.tcherepnin.com/alex/comps_alex.htm#misc, on the Tcherepnin Society webpage.

***See the following YouTube video for views inside and outside of the Romanian Pavilion in 1939 as well as sample musical performances (including the “popular Romanian recorder” Tcherepnin mentions in the interview) that inspired the then forty-year-old composer to create his Tzigane for the AAA decades later in his late 60s:

Participarea Romaniei la New York World's Expo 1939 - Maria Tanase, Grigoras Dinicu si Ion Jalea https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URfBPSz_wPw

The AAA Composers' Commissioning Committee welcomes donations from all those who love the classical accordion and wish to see its modern original concert repertoire continue to grow. The American Accordionists' Association is a 501(c)(3) corporation. All contributions are tax deductible to the extent of the law. They can easily be made by visiting the AAA Store at https://www.ameraccord.com/cart.aspx which allows you to both make your donation and receive your tax deductible receipt on the spot.

For additional information, please contact Dr. McMahan at grillmyr@gmail.com

2025 AAA 87th Anniversary Festival Daily ReportsJuly 10-13, 2025 Latest NewsMario Tacca, Mary Mancini AAA fundraiser tickets now available. 2025 AAA Elsie M. Bennett Composition Competition 2025-2027 AAA Executive Board take office 1st January. AAA History ArticlesHistorical Articles about the AAA by AAA Historian Joan Grauman Morse Music CommissionsHistorical and analytical articles by Robert Young McMahan. Recent articles:

AAA NewslettersLatest newsletters are now online. |